by Grace Pusey

Standing in front of Taylor Hall, Grace Pusey and Emma Kioko give a Black at Bryn Mawr tour to Professor Linda-Susan Beard’s Tuesday morning class. (Credit: Monica Mercado)

To date, Emma Kioko and I have given five tours to more than sixty students, staff, faculty, alumnae, trustees, and members of the local community. There are three more public tours scheduled for the semester; happily, two of these are tours we had to add to accommodate the overwhelming volume of interest in the project. I will also be offering a presentation on my digital walking tour at the Greenfield Center‘s “Women’s History in the Digital World” conference at Bryn Mawr College on May 21. The groundswell of support for Black at Bryn Mawr, I argue, is a testament to its necessity to the College community, and the positive feedback we’ve received on this blog (with its readership of 1,300+ strong) speaks to its value as a replicable model for similar public history projects. Overall, my experience with Black at Bryn Mawr has been incredible.

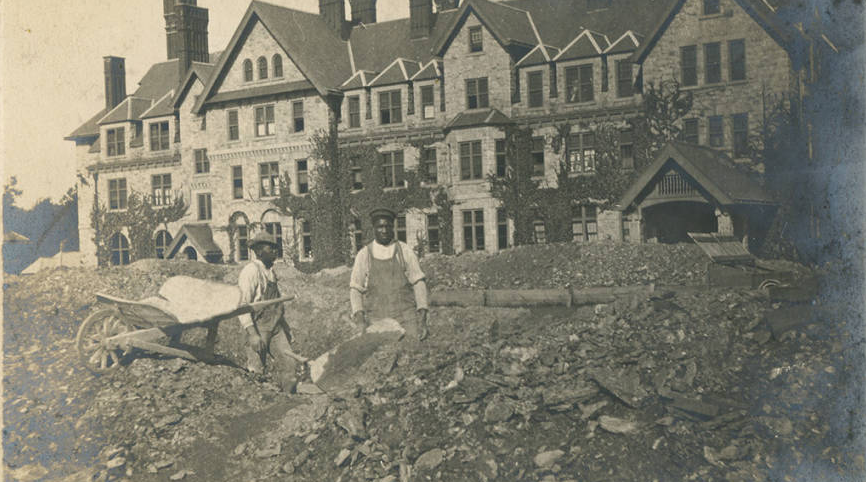

The project’s multidimensional approach to engaging the College community in understanding experiences of Black students, staff, and faculty throughout its history has deepened my awareness of Black history at Bryn Mawr and unsettled many of my assumptions about the spaces I move through and inhabit on campus. For example, I was unaware that servant tunnels even existed at Bryn Mawr prior to collaborating with Emma on a place-based approach to the College’s Black history, and had no idea that there was a cemetery behind English House, let alone one that belonged to a slaveholding Quaker family. I was not cognizant of the massive amount of unnamed, unseen, and now largely forgotten Black labor that went into building the College and curating its reputation as an aesthetically appropriate environment in which white women could socialize and study. I was unaware of M. Carey Thomas’ racist rhetoric and white supremacist beliefs and did not know that she envisioned Bryn Mawr not only as a place where women would be trained to become social, political, and cultural leaders, but as a place where white women would be groomed to inherit co-ownership of a role that had long belonged exclusively to white men: dominating over men and women of color. I feel like I have begun to grasp the gravitas of the fact that I walk daily through hallways and sit in classrooms designed to enrich the lives of women who look like me at the expense of Black women and other women of color.

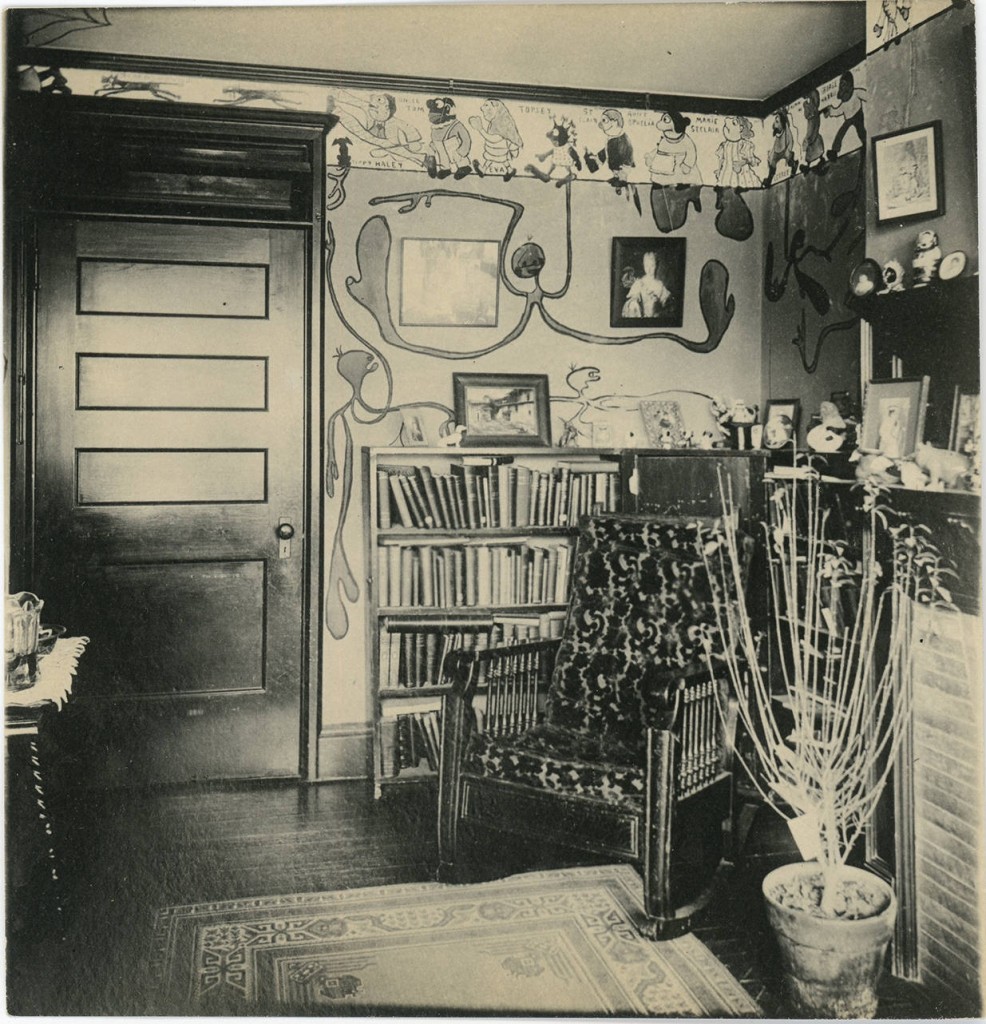

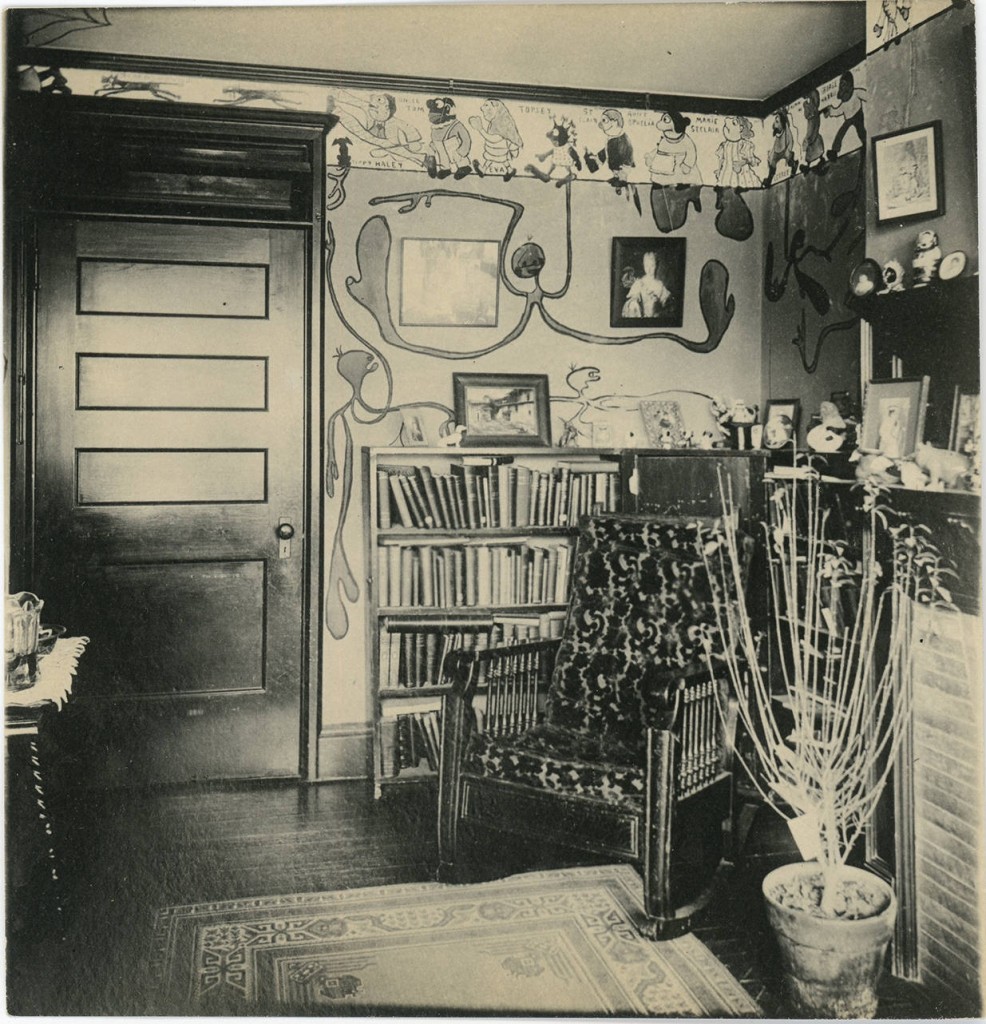

As I draft the forthcoming digital tour (which will debut in May), this realization hits me even more viscerally in ways that force me to stop and think. For example, I have encountered photographs of a student’s room with Uncle Tom and pickaninny caricatures painted on the walls, and know from archival research that Black maids would have vacuumed and changed the sheets in that room every day while living in abysmal conditions themselves. It reminds me that College housekeeping and dining services staff, of whom many, if not most, are Black, are much less able to take an hour out of their day for the walking tour, spare the time to read this blog, or see the digital tour. I am overjoyed by the unanimously positive responses to the walking tour we’ve received so far, but if I could rewind time and restrategize our outreach to these groups, I would.

Student’s dorm room, Merion Hall ca. 1902-1905 | Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA

Continue reading →