by Grace Pusey

Enid Cook was the first African American woman to obtain her degree from Bryn Mawr College. Prior to matriculating to Bryn Mawr, Cook graduated from Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C. (the first academically elite public high school for Black students in the U.S.) and spent one year at Howard University, where she was a straight-A student.1 She transferred to Bryn Mawr in 1927, where she majored in chemistry and biology.2 Six years after she graduated in 1931 she earned a Ph.D. in bacteriology in 1937 from the University of Chicago, where she went on to become a lecturer in the department of medicine from 1937-1944. In 1944 she married Arcadio Rodaniche, a doctor, and moved with him to Panama, where she served as the chief of the Public Health Laboratory for four years, then as a professor of microbiology at the University of Panama from 1954-1974. A highly gifted and pioneering woman in the sciences, Enid Cook published more than fifty articles in the field of arthropod-borne viruses over the course of her career.3

Cook’s exemplary academic record, however, did not preclude her from experiencing obstacles created to her admission to Bryn Mawr or from suffering social isolation and food insecurity stemming from the College’s stipulation that she reside off campus during her undergraduate career.4 She was fully aware of the challenges she would face at an all-white institution when she applied to the College, however, and refused to be deterred by them.

In a letter dated August 4, 1926 from Paul H. Douglas, an eminent Quaker activist and social reformer who later served as a U.S. Senator from 1949-1967, urging President Marion Park to admit Cook to Bryn Mawr, Douglas wrote:

“Some will undoubtedly raise the question as to whether it is not an act of kindness to Miss Cook to protect her from the possible discomfort which she would experience at Bryn Mawr, and that consequently it is for her own best interest that she be denied admission. May I respectfully suggest that this argument is unsound? Great pains have been taken to inform Miss Cook as to the reception she is likely to meet and she is thoroughly willing to accept any personal slights which she may experience at the hands of fellow students. In other words, she has made her choice and it seems to me that that should be sufficient for the Board.”5

Even though Cook knew that she would experience discrimination and prejudice at Bryn Mawr, she was adamant about applying.

Douglas, who by August 1926 had been advocating tirelessly on Cook’s behalf for almost five months, anticipated resistance on the part of the administration and tried to nip it in the bud. Benevolent racism was still racism, he reminded them; it was not in Cook’s “own best interest” to be denied admission to protect her from white students’ and professors’ prejudices.

Furthermore, the assumption that Cook was naïve to the difficulties she would face was not only false, but paternalistic. Cook’s ambition should be respected, Douglas insisted, not questioned.

In response to Douglas’ letter, President Park replied that Cook could apply, but only if she agreed to live off campus. Furthermore, she recommended Cook not apply at all, since it was unlikely that she would pass the entrance examinations with a score high enough to surpass the students already on the waiting list:

“I do not myself feel it would be wise to admit a colored student into residence at Bryn Mawr at the present moment. […] I think that in time a colored student or students can be admitted into residence but in a region of much prejudice and in a college where the prejudice is shared by many students my own judgement is that we should move more slowly than you suggest. […] I should perhaps add that Miss Cook’s passing the entire series of examinations at one time so successfully as to put her ahead of a long waiting list would seem to me in the case of any applicant very unlikely. With the further doubt of her admission I would strongly recommend her giving up this ordeal.”6

As President Park predicted, Cook did not score high enough on her entrance exams to move her application to the top of the pile. She scored 10.5 out of 15 points — high enough to secure her admission when she reapplied during the regular application cycle, but not high enough to put her ahead of the pool of students already wait listed when she initially applied (which was late spring 1926, after the Class of 1930 had been selected.)7 Charles Rhoads, son of Bryn Mawr’s first President, James Rhoads, was relieved to hear that Cook did not pass. “I was very glad to find […] that the problem of Miss Enid Cook’s application had solved itself by her failure to pass the examinations,” he confided in President Park in a letter dated October 6, 1926. But, he added, “I suppose it is inevitable that similar problems will arise in the future and we will have to learn by experience just how best to deal with them.”8

Letters like the one from Charles Rhoads to Marion Park reveal that the question as to whether Bryn Mawr would admit Black students was more than just a question. It was a “problem.” And it was a problem that the College knew it could not avoid forever. Nonetheless, the Board of Directors was slow to act. After Cook failed to ace Bryn Mawr’s entrance exams, the Board voted to refrain from making a formal decision regarding “the general subject of admission of negroes to residence,” but made plans to “discuss the matter […] before spring applications [came] in.”9 Despite their intention to discuss the admissions policy in December, they did not get around to it until April of the following year.

On April 18, 1927, a committee comprised of tenured faculty gathered to discuss whether Black students should be admitted to Bryn Mawr, and whether they should be permitted to attend as residents. Regarding the question as to whether Black students should be permitted to live on campus, the committee voted 19 nay to 4 yea. As to whether Black students could attend as non-residents, the committee voted 14 yea to 6 nay.10 Three days later (April 21, 1927) the Board of Directors voted to authorize President Park to “[…] reply to inquiries that colored students will be admitted to the College only as non-resident students.”11 In other words, Bryn Mawr’s admissions policy regarding Black students was by-request-only. The College made no attempt to make it publicly known that it was willing to accept Black students at all.

Thus, beginning with Enid Cook’s application and increasing steadily thereafter, there was a demand for the College to clarify its admissions policy regarding the admittance of Black students for the public. The steady increase in inquiries regarding Bryn Mawr’s admissions policy led Dorothy Straus, a Bryn Mawr Alumnae Association officer, to write to President Park in 1937,

“Though I hate to add another problem to an already overburdened College President, I find myself in the unfortunate position of having to have an answer to a question which is being put to me with considerable frequency, namely what is the official position of Bryn Mawr College on matriculating colored students. […] What answer shall I give? Or shall I evade the subject and allow the College to send its own answer by referring questions to someone in the College whom you may be good enough to designate; in other words, duck myself and let the College catch the ball?”12

Straus was not alone in wishing to “duck the ball,” as letters from Board members solicited by President Park to gauge their opinion on the matter illustrate. “I think for the interest of all our served, it would be wiser for any colored student to refrain from putting herself into so trying a position,” opined Board member Asa D. Wing in a letter to Marion Park regarding Enid Cook’s application. “But,” he backpedaled, “I do not want to be responsible for refusing to admit anyone on account of her color.”13 Similarly, Board member William C. Dennis felt that “Miss Cook ought to be advised not to attempt to enter Bryn Mawr and not to push the question of principle to an ultimate decision,” and added, by way of justification, that “[…] there is more opportunity for real service in educating the white girls and excluding a very occasional negro to whom other good colleges are open.”14 Rutle W. Porter felt that “Bryn Mawr would sink in [his] estimation” if Cook were required to live off campus, but acknowledged that it was “easy for [him] to say this and that the responsibility for difficult adjustments and meeting criticism [would] come on [President Park.]”15 Nonetheless, he insisted that he would support Park “in accepting that responsibility.”16 Conversely, alumna Anna B. Lawther felt strongly that Bryn Mawr should not accept Black students at all. “I feel sure that a colored girl would be made unhappy if she were allowed to live in residence and […] a great many students would resent her presence,” she wrote, and added anecdotally, “Personally I should not like to be forced to accept a colored girl as a companion at table for a year or part of a year, and I should not want to be as uncivil to her as I should feel.”17

Current students were not consulted for their opinion on the admissions policy, and once Cook was admitted to the College, it would have been gauche for the administration to conduct a formal survey of the student body. A letter addressed to Mrs. Talbot Aldrich from the Acting President of the College in July 1930 yields insight into students’ attitudes toward the prospect of a Black student living in residence, however. Responding to Aldrich’s inquiry about Bryn Mawr’s residency policy on behalf of another Black student, Lillian Russell (who graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1934), the Acting President wrote:

“We decided last spring that we would not offer Enid Cook a room for her senior year because as far as I was able to sound out student opinion such an action would have aroused a good deal of hostility and made her position worse rather than better. However, the presence of two colored girls in the college, one of whom was of an easier and more friendly disposition than Enid Cook’s, might change the situation and in another year the Directors might decide to admit her.”18

It seems ironic that Enid Cook’s disposition was described as difficult and unfriendly given that white students were, at least in the Acting President’s estimation, hostile to her presence. Cook’s admission to the College seemed to not make a difference in students’ attitudes toward Black students. Because of the persistent racism Cook experienced, the Acting President advised Mrs. Aldrich

“[…] that we should try to dissuade colored girls from coming here for their own sake and advise them to go to one of the New England colleges or to Cornell where their presence will undoubtedly be accepted in a more matter of course way and there would inevitably be less to make them self conscious with regard to their race and social standing.”19

The letter from the Acting President to Mrs. Talbot Aldrich demonstrates clearly that the “protection” argument Paul Douglas anticipated and argued against in his letter advocating for Enid Cook’s admission was redeployed to discourage more Black students from applying. The fact that Enid Cook experienced racism at Bryn Mawr was not condemned by the administration, but was used instead as grounds for other Black students’ exclusion. When Bryn Mawr realized it could not keep Black students out, it tightened its restrictions on non-resident students, stipulating that non-residents could live only “with their families in the immediate neighborhood.”20 This stipulation also proved weak, as a memo to President Park dated January 1940 regarding a prospective Black student from Washington suggests: the memo asked if Park wished for a Miss Ward “to put [the rules and regulations regarding non-residency] any more strongly” in order to discourage the student from applying.21

Perhaps the administration would have taken a different tack had they heeded Paul H. Douglas’ words in a letter addressed to President Park on August 30, 1926:

“It does not seem to me that any college should merely reflect the prejudices of the community about it or even of the student body within it. Are not colleges meant as institutions to overcome prejudices and to transform public opinion on such matters as these? Merely to conform to prejudices robs the college of one of the chief reasons for its being. Personally I should hate to see Bryn Mawr adopt the easy way in order to avoid the possible discomfort which a stand for the equality of human beings would entail.

“I do not mean […] to sound self-righteous, but it does seem to me to be a somewhat bitter paradox that after struggling to overcome the prejudices which men had against women, [Bryn Mawr] should be inclined to succumb to the prejudice which whites have against the blacks. Is not the human-being the important thing, irrespective of sex or color?”22

But the administration’s repeated attempts to discourage Black students from applying demonstrate that Douglas’ arguments did not prevail. Instead, Bryn Mawr chose to let the racism of its white student body dictate its admissions policy toward Black applicants, to insulate their privilege instead of interrogating it, and forfeited the opportunity to transform public opinion by taking a concrete stand for the right of Black women to the same educational opportunities as white women.

Unfortunately, the archival record offers little insight into Cook’s own experiences of the College. What we do know, based on Marion Park’s letters to Paul H. Douglas and his wife, Emily T. Douglas, is that prior to Cook’s admission the only education available to Black women at Bryn Mawr were classes taught by students to College maids.23 One wonders what witnessing the steep power differential between white women and Black women, coupled with Bryn Mawr’s indifference to the racism Cook experienced at the hands of the same white students entrusted with educating Black maids, had on Cook’s own experience of her collegiate education.

The absence of Cook’s perspective from the archive is perhaps understandable, given that the documents pertaining to her attendance were filed for administrative purposes only. It does, however, bring to light a difficulty central to this project. Our mission is twofold: first, to “unearth” — or make accessible — Black experiences of the College; and second, to analyze how Bryn Mawr has chosen to record, remember, and represent the history of its engagement with racism. But perhaps these two things are fundamentally opposed, or at the very least, at odds with each other. That is, because the documents available to us in the archives are overwhelming “white” (written by white correspondents, curated by white staff, etc.), it is difficult to know what Black students experienced themselves without resorting to speculation. The problem is a structural one: the parameters of our ability to seek out and interpret Black experiences at Bryn Mawr are delineated, especially but not uniquely in the case of Enid Cook, by the mechanisms of remembering constructed by white authorities. The silences surrounding Cook’s own experiences of the College are significant because they point to a fundamental challenge to one of the core aims of this project: our access to historical knowledge about Black experiences at Bryn Mawr is limited by its filtration through a white lens.

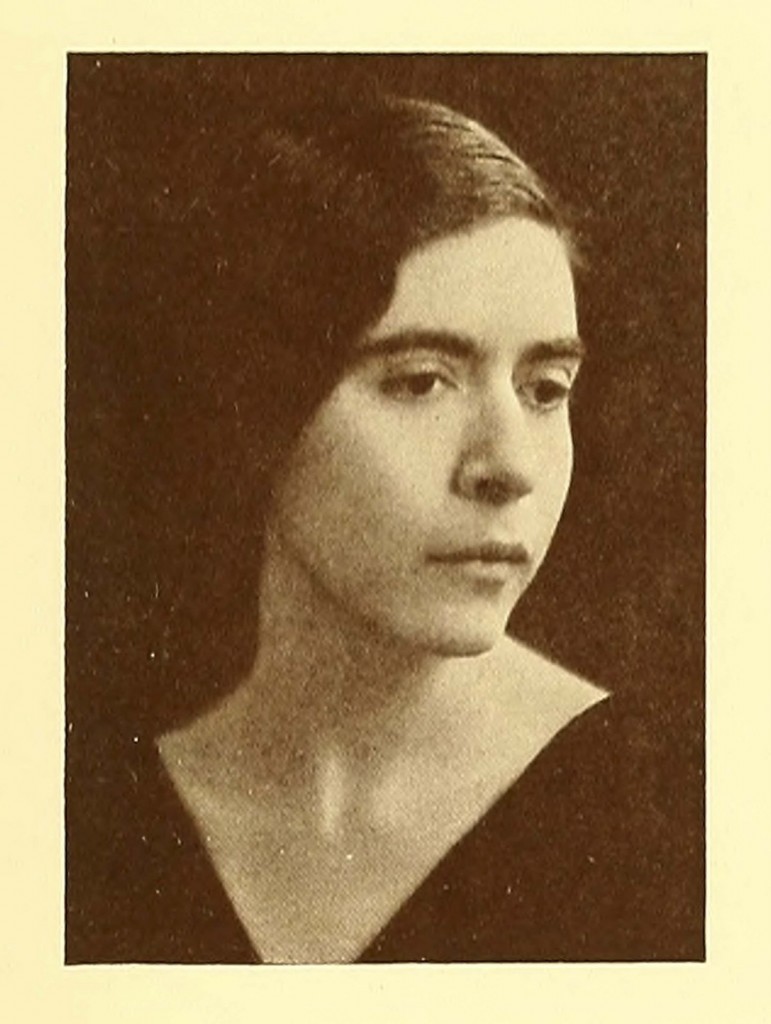

Photo credit: “Enid Cook,” The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education, accessed February 9, 2015, http://greenfield.brynmawr.edu/items/show/2943.

- Emily T. Douglas to Marion Park, April 3, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Anne L. Bruder, “Enid Cook, Class of 1931.” Offerings to Athena: 125 Years at Bryn Mawr College (Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA: Friends of the Bryn Mawr College Library, 2010): p. 107. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Acting President of the College to Mrs. Talbot Aldrich, July 18, 1930, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Paul H. Douglas to Marion Park, August 4, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Marion Park to Paul H. Douglas, August 22, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Bryn Mawr College Board of Directors to Asa D. Wing, September 25, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Charles Rhoads to Marion Park, October 6, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Memorandum concerning the admission of colored students (in connection with Miss Enid Cook’s application), October 21, 1926, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Tenured faculty meeting vote, April 18, 1927, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Board of Directors meeting vote, April 21, 1927, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Dorothy Straus to Marion Park, March 25, 1937, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Asa D. Wing to Marion Park, August 8, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IBD3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- William C. Dennis to Marion Park, September 7, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IBD3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Rutle W. Porter to Marion Park, September 2, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IBD3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Anna B. Lawther to Marion Park, September 5, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IBD3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Acting President of the College to Mrs. Talbot Aldrich, July 18, 1930, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Dr. Mildred Fairchild to Dean’s Office, April 16, 1942, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Memo dated January 1940, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Paul H. Douglas to Marion Park, August 30, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Marion Park to Mrs. Paul H. Douglas, April 27, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students — Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

Pingback: Black Labor at Bryn Mawr: A Story Imagined Through Census Records, 1880-1940 | Black at Bryn Mawr

If you wish information on Enid Cook’s experiences at Bryn Mawr why don’t you interview her husband Arcadio Rodaniche? You can get contact information for him from his web site (he is an artist).

Dear Mary Jane,

Thank you for your note, which I’ll pass along to Grace and Emma. We hope the project might continue on after they graduate next month.

Best,

Monica Mercado

Director, The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education, Bryn Mawr College

Pingback: “Monument Lab” Reflections | Black at Bryn Mawr

The artist Arcadio Rodaniche is not Enid’s husband (were her husband to be alive he would have more than 100 years), but a nephew of his husband. I was in touch with him (in fact it is his wife that answers email on his behalf), and apparently they do not know much about Enid. In fact, she referred to me to this webpage, which I had already visited. I would like to kno the years of birth and death of Enid, do you know them?

Dear Mercè,

Thank you for your note; you’re correct, Rodaniche is Enid’s nephew, and he and his wife have been in conversation with the College since last summer, when the possibility of naming the space on campus for her first came up. We are grateful for their enthusiasm. –MM