by Grace Pusey

Emma and I commenced our research on Black history at Bryn Mawr with a file labeled “Park Students – Negro” in a box of papers pertaining to Marion Park’s presidency housed at Bryn Mawr College Special Collections in Canaday Library. Marion Park was President of the College from 1922-1942, and though her administration was not the first to handle the “question” of Black students’ admittance to Bryn Mawr, it was the first to craft admissions policies that set a precedent for the admission of Black students to Bryn Mawr as non-residents.

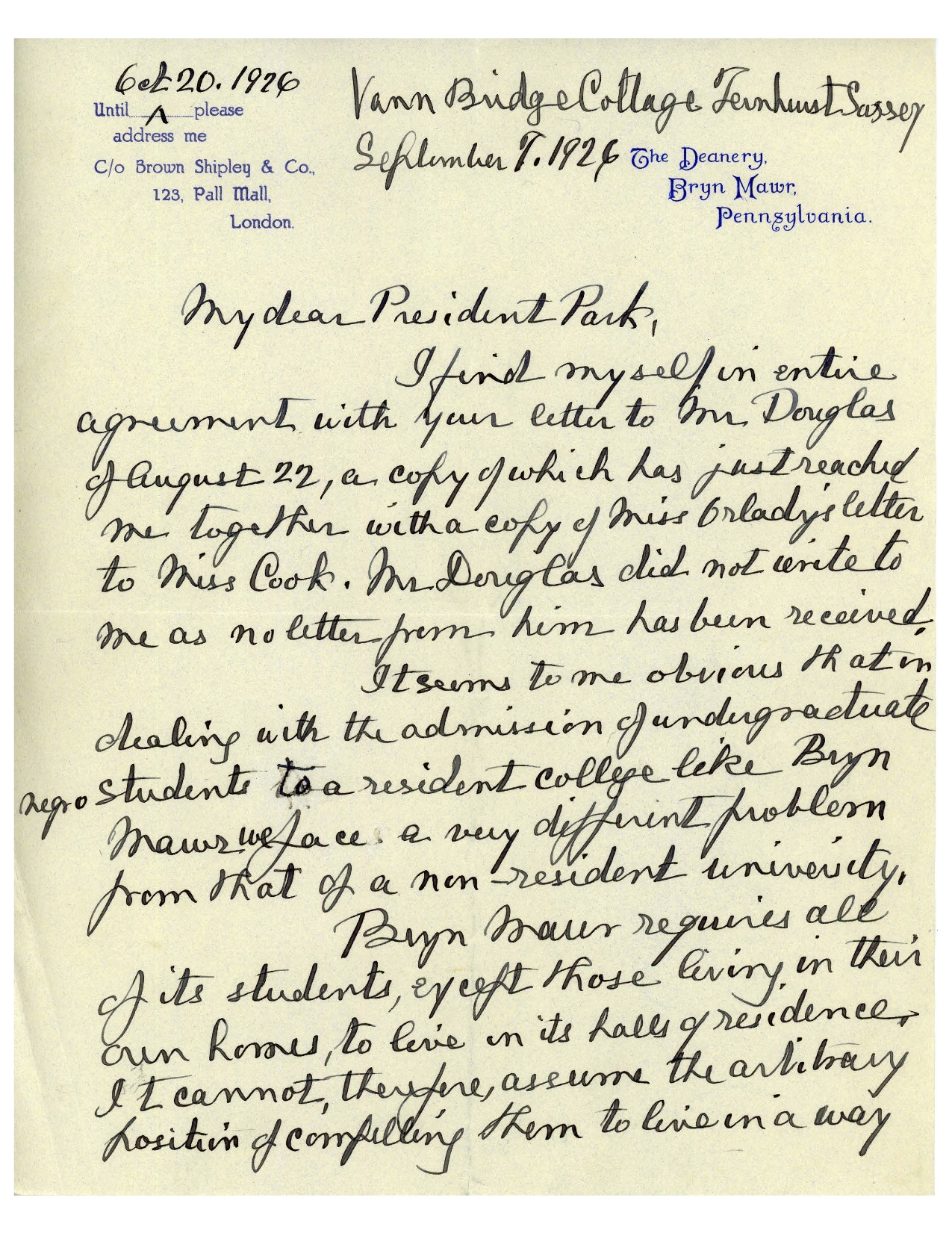

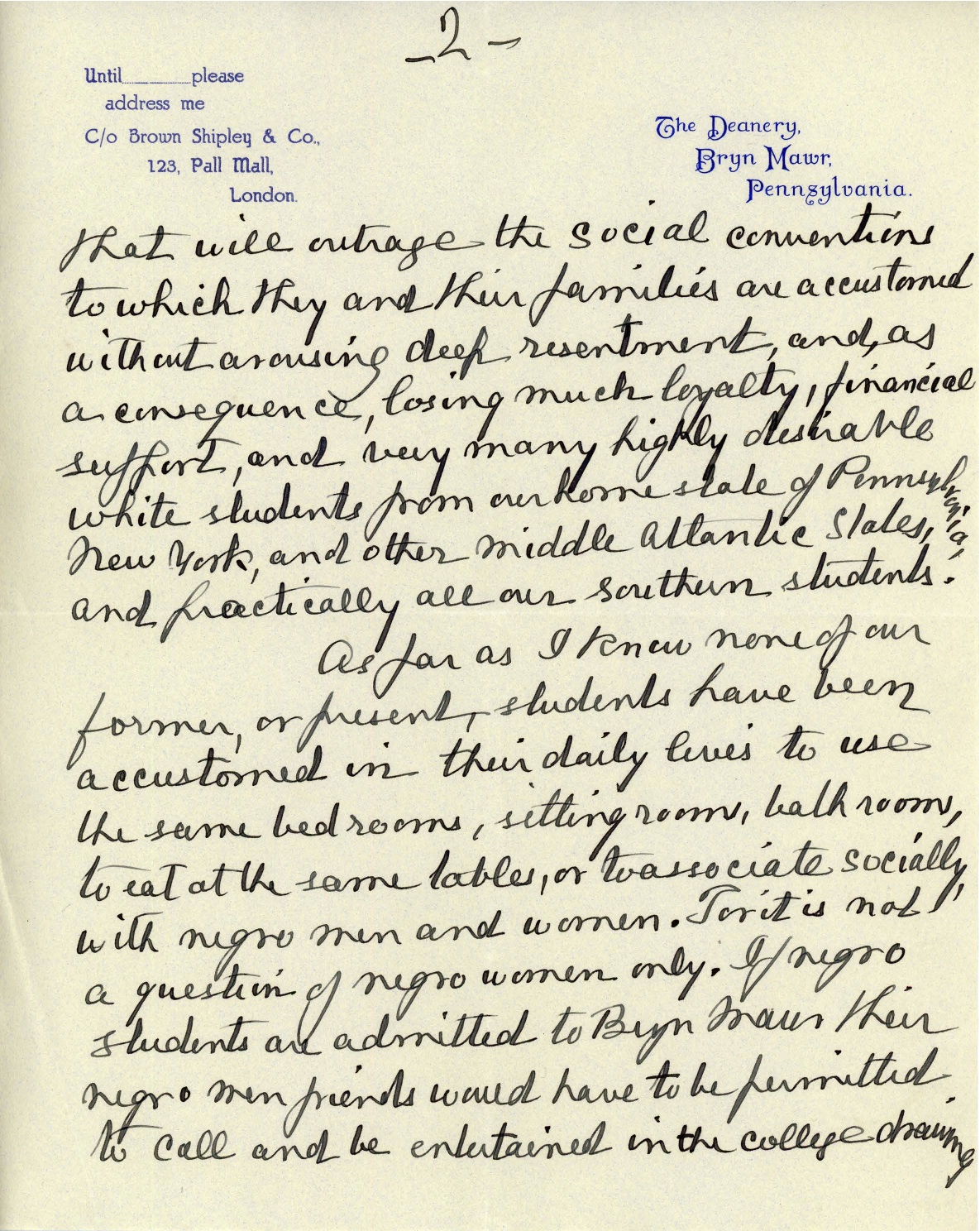

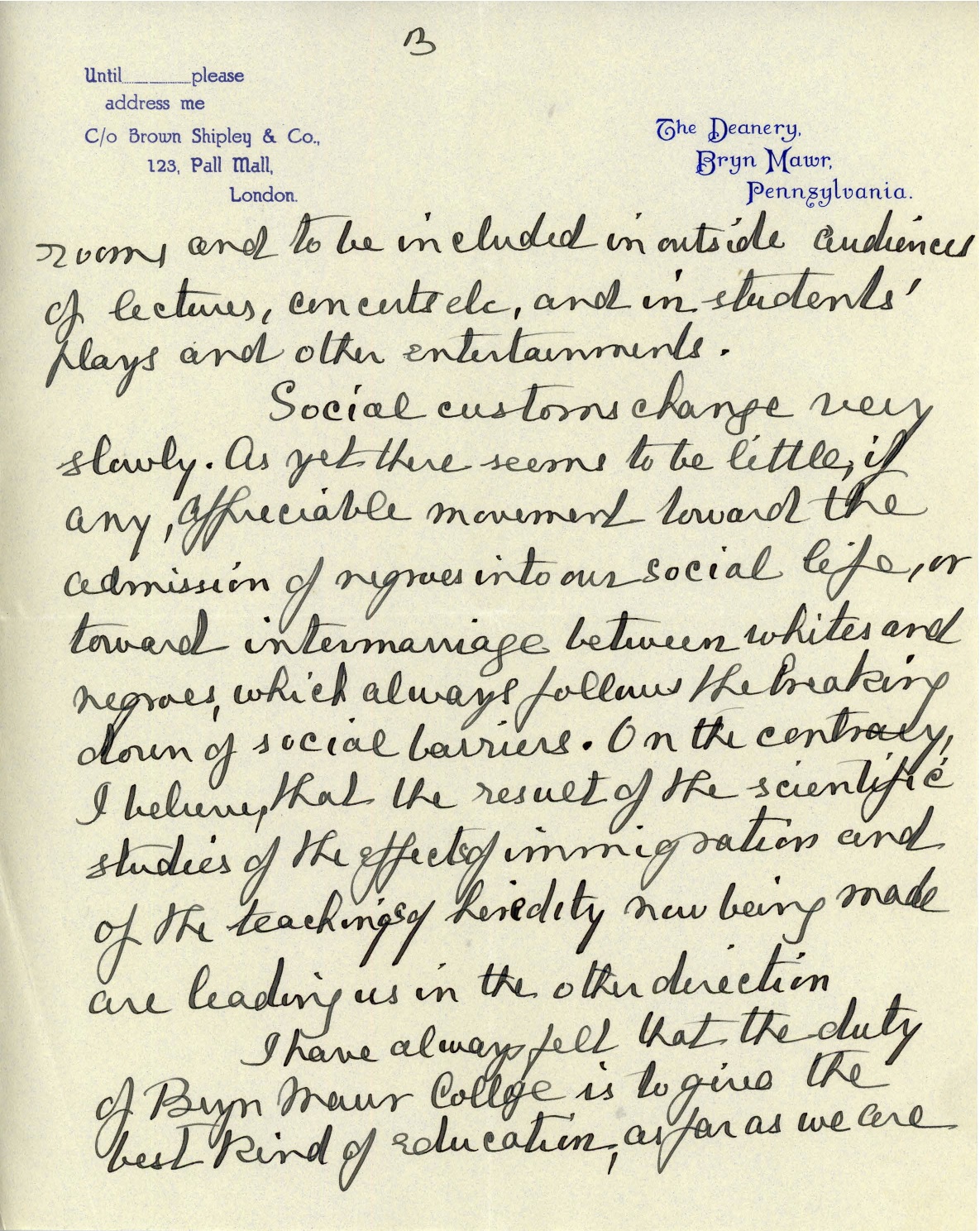

In response to a compromise proposed by President Park that Black students could attend Bryn Mawr, but only if they lived off campus, M. Carey Thomas (who served as the College’s second President from 1894-1922 and remained an influential College voice after her retirement) wrote a letter to Park dated September 7, 1926 expressing her support. After all, she opined, permitting Black students to live in residence alongside white students would “[…] outrage the social conventions to which [white students] and their families are accustomed,” and such a policy could not be carried out “[…] without arousing deep resentment, and, as a consequence, losing much loyalty, financial support, and very many highly desirable white students from our home state of Pennsylvania, New York, and other Middle Atlantic states, and practically all our Southern students.” Moreover, Thomas insisted that “[…] there seems to be little, if any, appreciable movement toward the admission of negroes into our social life […]. On the contrary, I believe, that the result of the scientific studies of the effects of immigration and of the teachings of heredity now being made are leading us in the other direction.”

In other words, Thomas believed that modeling social reform was less vital to the College’s mission than securing financial backing bequeathed to the institution by white students and families who relied on Bryn Mawr’s reputation to bolster and perpetuate their elite status in white society, especially given that “scientific studies of the effects of immigration and of the teachings of heredity” engendered doubt that social reform would prove necessary or valid at all in the long term. Admitting Black students to Bryn Mawr as non-residents only would appease advocates of social reform, at least temporarily, while minimizing the risk of alienating Bryn Mawr’s key financial constituents.

The non-residency stipulation for Black students’ admission was a noncommittal answer to the question of whether or not Black women should be entitled to the same educational and social opportunities as white women. To the question of social opportunities, Bryn Mawr’s response was a firm “no.” Black students’ exclusion from campus life was designed to prevent them from socializing with white students as much as possible, and preferably not at all. To the question of educational opportunities, Bryn Mawr extended a reluctant “yes” that could be — and in fact, later was — rescinded gradually without reneging on established precedent by manipulating the rules and regulations imposed on students residing off campus. (Emma and I will elaborate on this in forthcoming posts.)

The letter from M. Carey Thomas to Marion Park demonstrates that, even with the implementation of reforms that permitted Black students to earn degrees from Bryn Mawr for the first time in the College’s history, the administration’s prerogative was not progress, but appeasement.

A scanned copy of the letter and a typed transcription after the jump.

My dear President Park,

I find myself in entire agreement with your letter to Mr Douglas of August 22, a copy of which has just reached me together with a copy of Miss Orlady’s letter to Miss Cook. Mr Douglas did not write to me as no letter from him has been received.

It seems to me obvious that in dealing with the admission of undergraduate negro students to a resident college like Bryn Mawr we face a very different problem from that of a non resident university.

Bryn Mawr requires all of its students, except those living in their own homes, to live in its halls of residence. It cannot, therefore, assume the arbitrary position of compelling them to live in a way that will outrage the social conventions to which they and their families are accustomed without arousing deep resentment, and, as a consequence, losing much loyalty, financial support, and very many highly desirable white students from our home state of Pennsylvania, New York, and other Middle Atlantic states, and practically all our Southern students.

As far as I know none of our former, or present, students have been accustomed in their daily lives to use the same bedrooms, sitting rooms, bathrooms, to eat at the same tables, or to associate socially with negro men and women. For it is not a question of negro women only. If negro students are admitted to Bryn Mawr their negro men friends would have to be permitted to call and be entertained in the college drawing rooms and to be included in outside audiences of lectures, concerts etc, and in students’ plays and other entertainments.

Social customs change very slowly. As yet there seems to be little, if any, appreciable movement toward the admission of negroes into our social life, or toward intermarriage between whites and negroes, which always follows the breaking down of social barriers. On the contrary, I believe, that the result of the scientific studies of the effects of immigration and of the teachings of heredity now being made are leading us in the other direction.

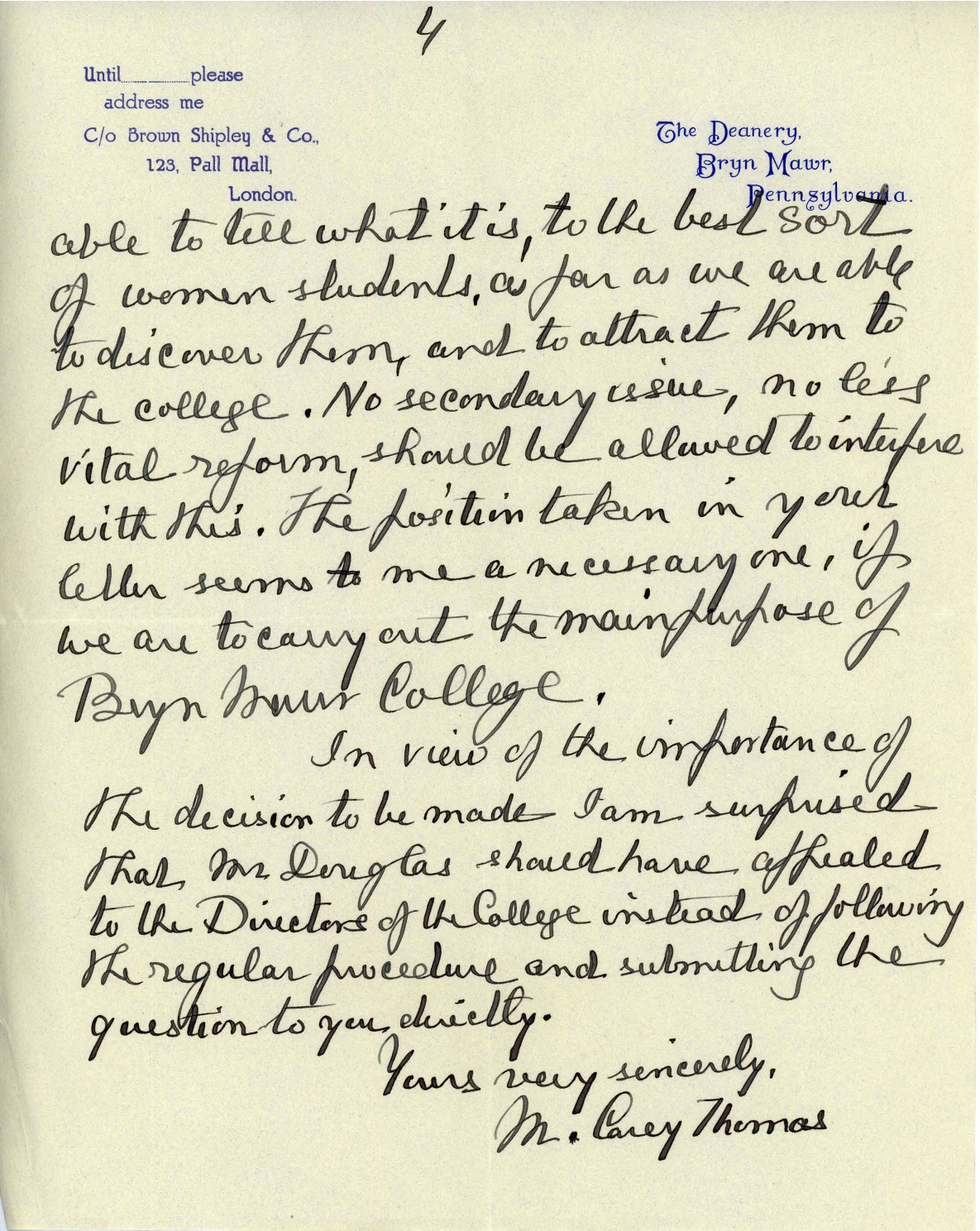

I have always felt that the duty of Bryn Mawr College is to give the best kind of education, as far as we are able to tell what it is, to the best sort of women students, as far as we are able to discover them, and to attract them to the college. No secondary issue, no less vital reform, should be allowed to interfere with this. The position taken in your letter seems to me a necessary one, if we are to carry out the main purpose of Bryn Mawr College.

In view of the importance of the decision to be made I am surprised that Mr Douglas should have appealed to the Directors of the College instead of following the regular procedure and submitting the question to you directly.

Yours very sincerely,

M. Carey Thomas

M. Carey Thomas to Marion Park, September 7, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students – Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Pingback: Black Labor at Bryn Mawr: A Story Imagined Through Census Records, 1880-1940 | Black at Bryn Mawr

Pingback: Grace’s Reflections on Black at Bryn Mawr | Black at Bryn Mawr

Thanks for the info. My Afr American daughter has selected Bryn Mawr as her first choice of schools for fall 2016. This is great sfuff!

Dear Arlene,

Thank you for reading the blog! If you’re back on campus, do let us know — our facebook page is https://www.facebook.com/blackatbrynmawr/

Best,

Monica

I am curious about a specific African American student of Bryn Mawr back in 1901. Her name was Miss G. E. Fowler. I am wondering if she was the same Miss G. E. Fowler who performed as a Soprano in the Famous Canadian Jubilee Singers? (She would have been with the group around the same time as the famous actor Charles Sidney Gilpin.) Your Miss Fowler was the leader of the Girls’ Fire Brigade at Bryn Mawr back in 1901. But were these two Miss G. E. Fowlers the same person? If you had a Miss G. E. Fowler who was a remarkable singer or even if your school had a highly regarded singing program then we possibly have the same person.