by Grace Pusey

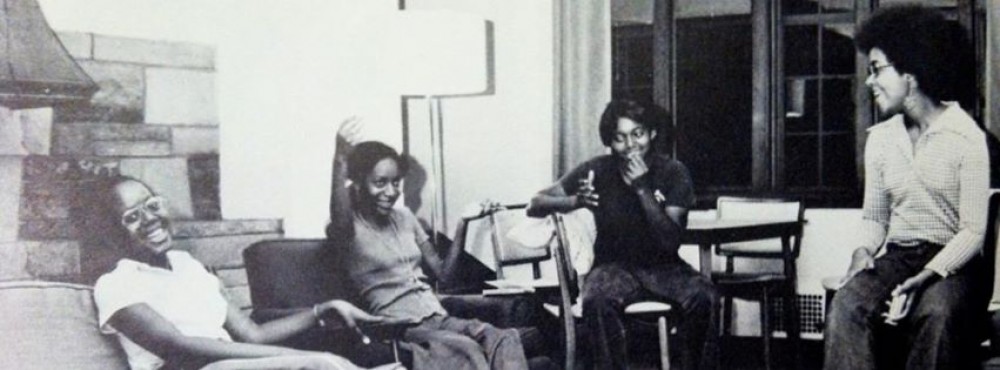

Bryn Mawr College President Kim Cassidy and students Grace Pusey ’15, Khadijah Seay ’16, and Danielle Cadet ’16 (August 31, 2015). Photo credit: Bryn Mawr College Communications.

At Fall Convocation on Monday, August 31, 2015, President Kim Cassidy announced that the residence hall and cultural center built to replace Perry House — the residence hall and cultural center that African American women fought for and won in 1972 (which later also housed members of Mujeres and BACaSO, campus affinity groups founded by and for Latina, African, and Caribbean students) — has been named the Enid Cook ’31 Center in honor of Enid Appo Cook, the first African American woman to graduate from Bryn Mawr College. After President Cassidy shared this news with an audience of students, staff, and faculty packed into Goodhart Hall, I joined Enid Cook ’31 Center co-presidents Khadijah Seay and Danielle Cadet (both Class of 2016) at the Center’s dedication. President Cassidy made a few remarks explaining why Bryn Mawr had chosen to name the Center after Enid Cook and acknowledged Khadijah and Danielle for their hard work and visionary leadership on the Relaunching Perry House Committee. She also thanked me for the essay I wrote on Enid Cook for the Black at Bryn Mawr project, which proved instrumental to the College’s decision to name the building in her honor.

When the festivities ended, I went home and wrote a heartfelt Facebook post about how meaningful the day had been to me. Monica emailed me the next morning to say that she had been moved by what I wrote and asked if I would feel comfortable blogging it, since we have used this space to toggle back and forth between historical research and reflections on the meaning of that research. I agreed; since then, I have been staring at a blank screen, trying to figure out how to repackage what I wrote then for the readers of this blog. What I shared with my friends on Facebook suddenly seemed embarrassingly sincere. Rather than revising my original post, however, I have decided to share it as it was written. It remains the most candid summary of my feelings about the experience, and I cannot think of a way to suppress the emotion behind it without minimizing how truly significant the dedication ceremony was to me. I wrote: Continue reading