by Grace Pusey

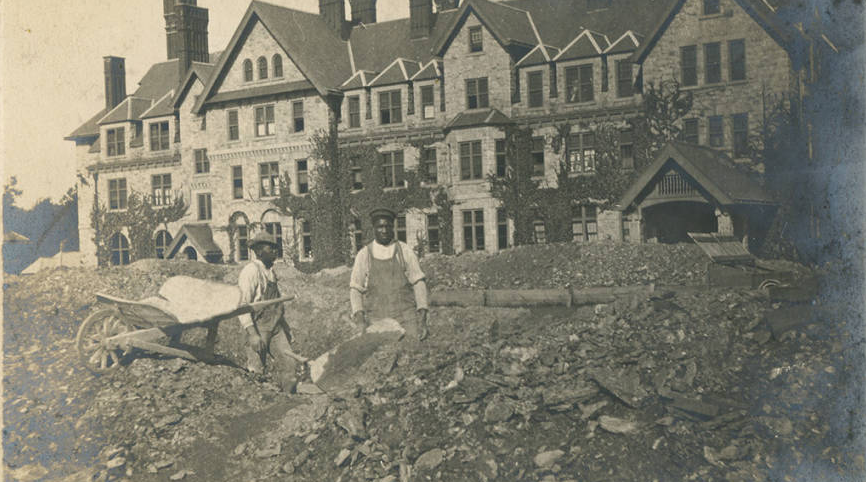

Two laborers working on Merion Hall ca. 1903. | Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

During my Historical Methods seminar on Monday, Professor Sharon Ullman requested that I write a post discussing the methodology I used for “Black Labor at Bryn Mawr: A Story Imagined Through Census Records, 1880-1940.” Conspicuously absent from my essay, she noted, was any mention of a group of College employees who migrated from a small town in Tennessee to Bryn Mawr over the course of several generations to work as maids. I was aware of the story of these maids when I conducted research for my post, but I did not write about them because I was unable to corroborate the story using the sources available to me. Because of this omission, Professor Ullman felt my essay made the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr seem like a closed narrative. I did not draw enough attention to gaps in historical understanding and knowledge that exist due to a dearth of information available on the topic. Instead, I glossed over these gaps or omitted them from my narrative entirely. My goal here is to offer a corrective to my original narrative by providing a brief overview of my research methodology.

Where are the Women from Tennessee?

A group of College employees migrates from a small town in Tennessee to Bryn Mawr over the course of several generations to work as maids: if true, it’s an extraordinary story. Multiple generations of women from the same family working at Bryn Mawr is certainly unique in the College’s history. Some of the servants listed in the censuses I consulted shared surnames, but when I compared their ages and places of origin, I found that few were related. Furthermore, there were no Black servants at Bryn Mawr College either from Tennessee or with parents from Tennessee listed in the 1940 census, which is the most recent census available to the public. In the early 1990s, a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow in one of Professor Ullman’s courses did an oral history project with one or more of the staff members who belonged to this family, but that student no longer has a copy of her project. The story of the maids from Tennessee is now more or less lost to history.

It is possible that the story has been remembered inaccurately. The maids may not have been from Tennessee, but from another Southern state. Other Black workers at Bryn Mawr listed in the 1940 census hailed from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Another possibility is that the family lived outside the College’s census enumeration district. If they lived outside the College’s census enumeration district, they would not have been recorded as College employees. This is arguably a strong likelihood, since Bryn Mawr offered competitive wages for domestic laborers in comparison to other area employers. These wages were, nevertheless, still low; but by pooling resources the family may have been able to afford their own home. The women could, of course, have opted out of the census, as census participation is not required by U.S. law. They might have migrated to Bryn Mawr after 1940, in which case we would have to wait until 2020 to look for them in 1950 census data. Yet another possibility — and maybe a likely one, as I explain below — is that they simply were not counted in the 1940 census.

Problems with Bryn Mawr Census Data

In 1940, the national net count of African Americans was so grossly underestimated that the Census Bureau developed a new system of measuring national net undercount in response.1 This system, Demographic Analysis, has been used as an independent check on census accuracy ever since. Demographic analyses use information from birth and death records, past censuses, and information on immigration to estimate national net undercount numbers. To this day, however, the national net undercount of African Americans has remained three percent higher than any other group surveyed by the Bureau since 1940.2 Saliently, the net undercount of Black workers at Bryn Mawr College was particularly bad.

If we can reasonably extrapolate from the difference between 1920 census data, which claimed there were 81 Black servants at Bryn Mawr College, and a 1926 article printed in The College News which stated the College employed 96 servants (of whom the majority were Black), then the net undercount for Bryn Mawr College was consistently significantly worse than the national average. Even when taking into account the estimated 3% margin of error affecting Black Americans in addition to the estimated national net undercount of 6-7% for pre-WWII censuses, the net undercount of Black workers at Bryn Mawr was off by approximately twice that percentage (15-20%.) We can assume that undercounting was a persistent problem at Bryn Mawr because the low count remains relatively stable, hovering in the mid-80s from 1900 to 1940, with the exception of a count of sixty-seven Black workers in 1930, which was probably a consequence of the Great Depression. (Fewer students attended Bryn Mawr during the Depression, which would correspond to a lower count of Black workers.) Mathematically speaking, the net undercount of Black workers at Bryn Mawr is still within the realm of “acceptable” error, at least in comparison to other census counts of Black Americans prior to 1950. If the count were off by more than 30%, the accuracy of the data would (by mathematical standards) seriously compromise the integrity of any ensuing historical analysis. (It is worth noting that a census undercount of 15-20% would be considered completely unacceptable by Bureau standards today.)

Does the higher net undercount of Black workers at Bryn Mawr in comparison to national net undercounts of Black Americans have serious consequences for an analysis of the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr? It depends on what we consider “serious consequences.” Again, the net undercount at Bryn Mawr is not so far off from the actual count that it renders the census data useless. It does, however, call into question the accuracy of census data for the College and makes the records relatively unreliable documents (or highly unreliable, depending on one’s perspective) to work with in reconstructing the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr.

When the Archive Isn’t Enough

But where else is there to look? In addition to census records, there are other databases of public records that may be helpful to reconstructing the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr. Via Tripod, College members can access American historical newspapers on Readex and search for African American news publications by geographic area. However, unless one knows the name of a particular person (or persons), their hometown, or other relevant biographical data, mining newspapers for information on the lives of Black laborers at Bryn Mawr is more or less a crapshoot. Moreover, my original census search came about because there are so few archived materials on the College’s Black labor history at Bryn Mawr Special Collections. Most of the materials that do exist are recent attempts to fill archival silences on the history of Black staff experiences at Bryn Mawr.3

The fact that I had to go beyond materials archived at Special Collections in order to research Black labor history at Bryn Mawr at all gestures to one of the major pitfalls of this project: the uneven power dynamics of the College Archives. The “diversity” box (9J) is, as Emma and I pointed out during our presentation on the Community Day of Learning, Special Collections’ kitchen junk drawer. In comparison to the neatly organized boxes of Presidents’ papers, the Diversity box overflows with marginalia from various student groups, diversity trainings, and College publications. The materials themselves lack structure; news articles about the 2014 Confederate flag hanging and response, for example, are stuffed in a folder labeled “1990.” There are no archived materials from Black faculty members because the first Black professor at Bryn Mawr, Professor of Sociology Robert Washington, is still here. Black staff are discussed in the archive, but they rarely represent themselves. Black students were the first to conduct oral histories with College staff in order to redress this oversight beginning in the 1990s, but accumulation of materials over the past 20-25 years has been slow.

Using census records, I was able to reconstruct a general picture of the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr, which had not been done before. However, in addition to the quantitative issues with census data detailed above, there are qualitative issues as well. To address this problem, future research on the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr will likely necessitate oral history projects with former staff. Furthermore, Special Collections will need to take steps toward a more aggressive collections process, asking College staff members to donate materials to the archive and making it more widely known that the archive exists to record their stories, too.

Who Gets to Write This History?

My previous point brings me to a dilemma central to an analysis of Black labor history at Bryn Mawr, and to the project more generally: who gets to write this history? One of my concerns about this project is its reach. Who reads this blog? Is this project — and its attempt to create multiple avenues to engaging with Black history at Bryn Mawr — accessible to College staff? Will future generations of Black at Bryn Mawr scholars be relegated to taking circuitous pathways to understanding Black labor history at the College, as I was, or will there be more information to them available in the archive? Will staff members themselves become historians of College laborers, taking the lead on how this history is collected, remembered, and represented by the institution?

The story of the women from Tennessee may be lost, at least for now. But future stories like it do not have to be. My hope for the future of the Black at Bryn Mawr project is that students, staff, and faculty continue to build on the work that Emma and I have done. I do not want anyone to read this blog, take the walking tour, or browse the forthcoming digital historical record and think that Black history at Bryn Mawr is a closed narrative. The work has only just begun. I will consider this project a success only if I can return to the College in five or ten years and see how other students, staff, and faculty members have continued to grow the project, incorporated it into College diversity training, and pushed it in new directions.

Note: Emma and I will be pulling some of the materials I discuss in this post (and in other posts) during our upcoming Friday Finds presentation in Special Collections from 4-5 pm on April 24. The presentation will be preceded by a Black at Bryn Mawr walking tour from 2:30-4 pm. We hope to see you there!

- “Reasons Behind Inaccuracies in the Census.” The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, accessed April 14, 2015, http://www.civilrights.org/census/accurate-count/inaccuracies.html. [↩]

- Howard Hogan and Gregg Robinson, “What the Census Bureau’s Coverage Evaluation Programs Tell Us About Differential Undercount,” report delivered at May 1993 Research Conference on Undercounted Ethnic Populations by the U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics, and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census, Washington D.C. Accessed April 14, 2015, https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/1993/conference.html. [↩]

- See the suggested reading list on the original “Black Labor at Bryn Mawr” post here: http://blackatbrynmawr.blogs.brynmawr.edu/2015/03/09/black-labor-at-bryn-mawr/. [↩]

Grace,

This is a wonderful reflection on theory and method, and it reminds me how important a common repository is, even for student work. How are we to know what important original research BMC students have done in the past on these untold histories — as in the case of the story of workers with Tennessee ties. How can instructors make those pathways to archiving new research possible?

For this reason, I remain continually impressed by your (and Emma’s) commitment to making your research public, even in a state you might feel is unfinished or incomplete — and you’re giving me more ideas for future conversations about build on this site after you and Emma have graduated. Thank you for sharing.

Pingback: Grace’s Reflections on Black at Bryn Mawr | Black at Bryn Mawr

Pingback: Black Labor at Bryn Mawr: A Story Imagined Through Census Records, 1880-1940 | Black at Bryn Mawr