A maid on the steps of Merion Hall ca. 1898. | Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

by Grace Pusey

Before Bryn Mawr: 1880-1885

Five years before Bryn Mawr College opened its doors in 1885 to young women seeking the kind of rigorous academic training that was then available only at a few elite institutions for men, only fifteen Black people resided in Lower Merion Township.1 Most were young, single men from Pennsylvania and its neighboring states — the youngest among them, a nine-year-old servant named George Taylor, was from New Jersey. There was only one Black family among the residents of Lower Merion Township in 1880, a married couple with five children.2

Mr. and Mrs. Penrose Hall were native Pennsylvanians, though Mrs. Hall’s parents immigrated to the state from Maryland.3 Mr. Hall served in the military during the Civil War and later became a carrier for the U.S. postal service while his wife stayed home to raise their two daughters and three sons.4 Neighbors probably listened for the familiar clip-clop of horse’s hooves as Mr. Hall made his daily rounds, hoping he might stop his carriage in front of their house to deliver a letter or parcel to them. Whereas Mr. Hall likely worked six days a week, rain or shine, his horse may have worked seven if he hitched her up to his mail buggy and drove his wife and children from their home on Belmont Road to First United Methodist Church in Roxborough on Sunday mornings.5 When Mrs. Hall buried her husband in the wide, flat field of Leverington Cemetery at Ridge and Lyceum Avenues in December 1888,6 perhaps her throat clasped at the thought of hearing the clip-clop of the mail carrier’s horse on the road again, knowing that from then on the driver would not be her husband.

During the final years of his life, Mr. Hall may have watched the rapidly changing landscape in Lower Merion Township with surprise and wonder from atop his four-wheeled perch. Perhaps his delivery route shifted to accommodate the newly-founded Bryn Mawr College in 1885, just a few short miles up the road from his home in Manayunk. Maybe he passed the College and thought of his little Bella and Laura, their bright and curious brown eyes lighting up as he taught them to read — Mr. Hall was probably a lettered man, since he was certainly a man of letters — and thought, Educating women! What a radical idea. Maybe someday they’ll open their doors to my daughters, too. Though he was far from wealthy, Mr. Hall had done well for himself after the War; at the very least, he was better off than his brother Oliver, who worked long, backbreaking days as a farm laborer and servant.7 Perhaps Mr. Hall was the sort of man who believed in progress.

But if hope for racial equality flickered even fleetingly in Mr. Hall’s mind, it was far from a reality at Bryn Mawr in 1885. If Mr. Hall did see Black people on Bryn Mawr’s campus before his death in 1888, it was only in roles of subservience to White students, staff, and faculty. By 1900, sixty-eight Black people resided on Bryn Mawr’s campus, most of them women, and all of them servants.8 They hailed from places both near and far: from Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, Virginia, Ohio, the Carolinas, Rhode Island, and even Canada. They had names like Josephine, Lulu, Alice, Eliza, Rose, Addie, Mamie, and Nadine. Most were young, single women who had come to work at the College alone; perhaps their families had settled in Philadelphia, or perhaps they left them behind. They were the forerunners of the Great Migration spurred by the World War fourteen years later, securing domestic jobs that would become increasingly scarce as their Southern sistren travelled northward by train, boat, and bus seeking work in factories, foundries, and private homes.

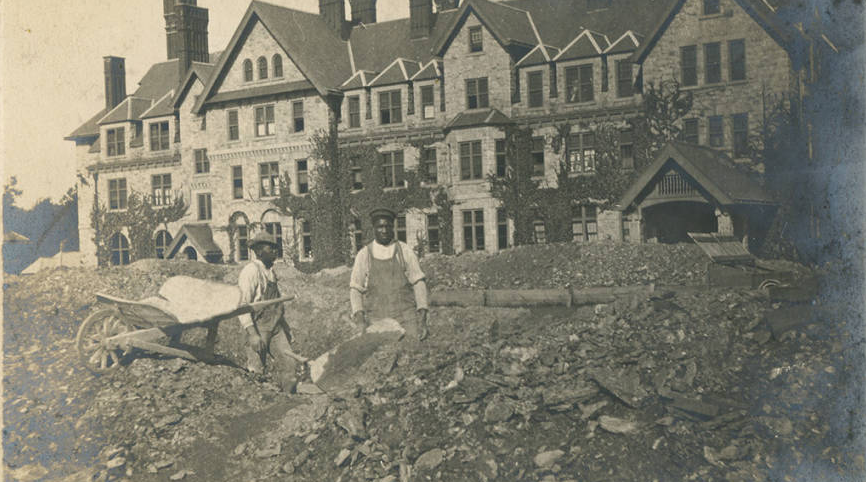

Two laborers working on Merion Hall ca. 1903. | Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Black Labor at Bryn Mawr, 1885-1940*

*Note: To date, U.S. federal census records are only public up to 1940.

The women worked as waitresses, cooks, chambermaids, parlor maids, bell girls, and servants; the men worked as porters and pantry men. Their lives were a flurry of steaming pots, clattering dishes, ringing phones, and fresh white linens. They worked their bones to a deep ache, every stair on their last climb up to their cramped quarters on the fourth floor of Merion Hall creaking beneath their tired weight. Pennsylvania labor law required the College to give servants twenty-four consecutive hours off per week — one full day — which Director of Halls Ellen Faulkner described in 1926 as something of an annoyance: “[…] we are always shorthanded for we have no relief maids,” she wrote, “nor can we consider adding them to our staff because of the additional expense and the impossibility of finding room for them in our servants’ quarters.”9 When Jessie Fauset, the first Black student at Bryn Mawr, attended the College for a month in 1901 before President M. Carey Thomas raised enough money for her to transfer to Cornell, one wonders what the maids might have thought of her presence. Did any of them get a chance to know Fauset during the brief time she spent living in a maid’s room on campus? What did they whisper to one another about her forced removal from the College when they bumped into each other in the laundry or in the supply closets? What opinions did they have, if they dared to have opinions at all? And when Fauset rose to prominence as a Harlem Renaissance author and poet in the 1920s, did any of them turn to her writing for a voice that could speak to them?

By 1910, the number of servants at the College had grown to eighty-seven, nearly twenty more than ten years before.10 Moreover, the 1910 census records of the College were better organized than the census conducted in 1900: it grouped lists of Black servants by the residence halls in which they lived under the names of their white supervisors, casting the racial hierarchy of relationships between Black and white workers into sharp relief. Typically a dormitory would be overseen by a white warden and head housekeeper, but sometimes a hall manager or secretary as well. Among Black workers, the census did not appear to differentiate between a chambermaid and a cook; lists of Black laborers were not ranked by the prestige of their duties. Eleven Black workers lived in Merion Hall; eleven lived in Radnor Hall; fourteen and sixteen lived in Denbeigh and Rockefeller Halls, respectively; and the largest group — twenty-seven Black workers — lived in Pembroke Hall. Eight lived and worked in the apartment houses in which College professors resided. Jen Rajchel’s digital exhibit, which uses floorplans to explore the relationship between dorm culture and domestic labor, quotes Margaret Bailey Speer (Class of 1922) as describing the maids’ living conditions as “dingy and horrid […] I don’t see why the maids stay for a minute.”11 Maids’ rooms were a far cry from students’ rooms, which Rajchel notes were frequently photographed and publicized in newspapers in order to satisfy a “deeply spectatorial curiosity” — and anxiety — about the lives of women scholars. Black workers were responsible for curating this aesthetically appropriate environment in which young, elite white women could socialize and study.

Interestingly, the 1910 census indicates that only one of President M. Carey Thomas’ seven personal servants was Black. The rest were white.12 The fact that most of Thomas’ servants were white is perhaps surprising, given her penchant for White supremacist rhetoric.13 Why would a woman with firm convictions about the inferiority of Black people choose to employ white women in jobs clearly demarcated elsewhere on campus for Black women only? A potential clue emerges from the 1930 census. In 1930, four white servants were listed as residents of Rockefeller Hall, where they served an unnamed “private family.”14 Presumably they were hired for a student residing in the dorm by the student’s parents. Their presence is the only instance recorded in the census of the College between 1900 and 1940 (the 1890 census was destroyed in a fire) of servants employed by a private family residing in a dormitory at all. Perhaps white servants were status symbols, given that they were probably paid higher wages than Black servants, or perhaps people like Thomas preferred white servants because they did not want to invite Black servants into their most intimate spaces, to allow them to have personal contact with them and their things. But even Helen Taft, daughter of U.S. President William Howard Taft and Bryn Mawr College dean, lived with four Black servants in Wyndham House during her tenure at the College.15 Why M. Carey Thomas chose to surround herself with white servants, if it was indeed a deliberate choice, remains a mystery.

In 1910 the ratio of Black workers to white faculty and staff was immensely disproportionate, with the number of Black employees at the College vastly outnumbering white ones. The ratio became slightly less disproportionate by 1920, but only by a hairbreadth: the number of Black servants decreased from eighty-seven to eighty-one. In 1930, the decade of the Great Depression, sixty-three Black servants were employed by the College, perhaps because the College could only afford to keep a limited staff or because fewer students could afford the school’s tuition fees, thereby decreasing the demand for Black labor on campus; but by 1940 there were eighty-five. Of course, U.S. federal censuses are only conducted every ten years, and therefore provide a limited amount of information where there is potential for much more. Moreover, it is probable that the census records underreported the number of Black workers at Bryn Mawr; for example, a reprinted article from the March 1926 Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin in Offerings to Athena: 125 Years at Bryn Mawr College suggests that there were in fact ninety-six servants at Bryn Mawr in 1926, fifteen more than the 1920 census indicates.16 But one thing remains clear: Black workers figured prominently in campus life, not only in terms of sheer volume, but in terms of the daily contributions they made to keep the campus running smoothly.

Another way in which the utility of census records is limited is obvious: they provide only a skeletal framework for imagining what Black servants’ lives were like. Photographs, memoirs, and personal letters are scarce. A November 15, 1922 article from the College News boasted that Bryn Mawr had a “reputation of giving its maids an opportunity to study so that working [at the College] would be a stepping stone to other work like nursing or stenography,” and indicated that the College had a night school and Sunday school for maids, as well as a Maids’ Club, where students and servants congregated twice a month to sew and discuss current events.17 This unusual consideration for the life of the mind of Bryn Mawr’s workers led the same student in 1922 to write that Bryn Mawr maids preferred the College over other places to work.18 As Enid Cook’s case demonstrates, however, the College supported the education of Black women only to a limited extent.

Maid serving students at breakfast ca. 1950s or 1960s. | Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Beyond Bryn Mawr: A Shifting Landscape

If Penrose Hall had not passed away prematurely at the age of forty-eight, he might have lived long enough to witness the changing landscape around Bryn Mawr in the late 1920s and early 1930s, when Enid Cook, Bryn Mawr’s first Black graduate, attended the College. Because the College would not permit Cook to live on campus, she lived first with Haverford professor Henry Cadbury and his family at No. 3 Haverford College Circle, one of the faculty houses on Haverford’s campus.19 The Cadburys had one Black servant, a 44 year-old woman from Virginia.20 For reasons she never disclosed to the College, Cook moved to 46 Prospect Avenue in her second year at Bryn Mawr.21 She lived as a boarder with three divorcees listed in the 1930 census as lodgers — two men and one woman — in a home owned by Mabel Tunnell, a forty-year-old Black widow from Delaware.22 All the residents in her boarding house, and on her block, were Black. In other words, at some point in the fifty years after Mr. Hall lived as one of the few Black residents of Lower Merion Township, Bryn Mawr developed its own Black neighborhood.

This development is unsurprising in the context of the Great Migration, when Black families from the South migrated to major industrial cities in the North to find work after WWI. Philadelphia’s Black population alone ballooned from 63,000 in 1900 to 220,000 in 1930, an increase of over 350%.23 When the Great Depression hit, migration slowed as one in every two Black Philadelphians faced unemployment. With de-industrialization and the passage of the G.I. Bill after WWII, places like Bryn Mawr became increasingly white as families of European immigrants who had once settled in the city relocated to Philadelphia’s suburbs, and the poverty rates among Black families skyrocketed as the city disinvested in Black neighborhoods. What did maids who took advantage of vocational training offered at the College do with their skills when the economy tanked and white employers allocated their scarce resources to hiring white workers over Black ones? Were they able to improve their and their families’ economic status despite the odds stacked against them? In what way is the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr connected to the history of Black labor in Philadelphia? What responsibility does the College have to acknowledge this connection? Furthermore, what might that responsibility look like?

Conclusions

Tim McMillan, creator of the Black and Blue Tour at UNC, describes colleges not just as “[…] a place in which to learn, but a place from which to learn.”24 What happens when we look at Bryn Mawr not just as a premier educational institution for women, where women were groomed for elite social, intellectual, and cultural leadership, but as a premier educational institution for women that relied intensively on White supremacist rhetoric and the entrenchment of a racial hierarchy that ensured a steady supply of Black labor to secure its elite status? Ancillary to Bryn Mawr’s promise of a first-class education was its ability to market a first-class lifestyle, which it continues to rely on in its marketing today. Who makes this lifestyle possible? Whose lifestyle(s) does Bryn Mawr set its image against? What sorts of values and expectations has Bryn Mawr’s long history of Black labor inculcated in the institution?

We tend to think of Black history as separate from the history of the College, or when we do consider it as part of the College’s history, we enunciate its origin point(s) around figures like Jessie Fauset and Enid Cook. But Black history has been part of Bryn Mawr’s history since its founding. Looking at the history of Black labor at Bryn Mawr opens doors to the sorts of deep, pressing questions about Bryn Mawr’s relationship to racial inequality that we, as members of the College community, must address.

Acknowledgement: I would like to extend a special thank you to Olivia Castello, Outreach and Educational Technology Librarian and Social Sciences Library Liaison, for giving me a brief-but-highly-informative lesson on how to read, navigate, and mine census records for useful data earlier this week.

Methodology

For more information, see A Note on Method: Researching ‘Black Labor at Bryn Mawr,’ April 16, 2015.

Suggested Reading

Dana Cooper and Fleta Blocker, “Interview with Fleta Blocker.” The Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education, July 27, 1995.

Jennifer Redmond, “Maids, Porters, and the Hidden World of Work at Bryn Mawr College: Celebrating Stories for Black History Month.” Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education, February 12, 2013.

Jen Rajchel, “Residing in the Past: Space, Identity, and Dorm Culture at Bryn Mawr College.” Digital Exhibit, Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education.

H.S. Burke, “Maid in Silence: The Hidden History of Bryn Mawr’s Housekeepers.” Serendip Studio, Walled Women 360, November 30 2012.

Maggie Caldwell, “Invisible Women: The Real History of Domestic Workers in America.” Mother Jones, February 7, 2013.

James Wolfinger, “African American Migration.” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Rutgers University, 2013.

- 1880 United States Census, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. [↩]

- 1880 United States Census, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania: p. 24, family 202, dwelling 195, lines 31-37; June 9-10, 1880. [↩]

- Ibid, lines 31-32. [↩]

- Ibid, line 31; and U.S. Civil War Draft Registrations Records, 1863-1865, Class I, Congressional District 3, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: p. 574, line 11; May and June 1863. [↩]

- The Hall children were baptized at First United Methodist Church on February 26, 1886. See Pennsylvania and New Jersey Church and Town Records, 1708-1985, First United Methodist Church Record of Baptisms: p. 475. [↩]

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates Index, 1803-1915, FHL Film No. 2079502, from originals held at the Philadelphia City Archives. [↩]

- 1880 United States Census, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania: p. 33, family 283, dwelling 276, line 47; June 14, 1880. [↩]

- 1900 United States Census, Bryn Mawr College, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. [↩]

- Ellen Faulkner, “The College Household,” reprinted from the Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin, March 1926, in Offerings to Athena: 125 Years at Bryn Mawr College, ed. Anne L. Bruder, Friends of the Bryn Mawr College Library, 2010: p. 103. [↩]

- 1910 United States Census, Bryn Mawr College, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. [↩]

- Jen Rajchel, “Residing in the Past: Space, Identity, and Dorm Culture at Bryn Mawr College.” Digital Exhibit, Albert M. Greenfield Digital Center for the History of Women’s Education, accessed March 6, 2015. http://brynmawrcollections.org/greenfield/exhibits/show/residinginthepast/dormcultureanddomesticity/maidsandporters. [↩]

- 1910 United States Census, Bryn Mawr College, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania: p. 4, lines 85-93; May 9-13, 1910. [↩]

- M. Carey Thomas to Marion Park, September 7, 1926, Letter, Marion Park Papers 1922-1942, Box 29 IDB3, “Park Students – Negro,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- 1930 United States Census, Bryn Mawr College, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania: p. 1, lines 42-45; April 2, 1930. [↩]

- 1920 United States Census, Bryn Mawr College, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania: p. 1, lines 1-5; January 8, 1920. [↩]

- Ellen Faulkner, “The College Household,” reprinted from the Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin, March 1926, in Offerings to Athena: 125 Years at Bryn Mawr College, ed. Anne L. Bruder, Friends of the Bryn Mawr College Library, 2010: p. 103. [↩]

- Column reprinted from the College News, November 15, 1922, in Offerings to Athena: 125 Years at Bryn Mawr College, ed. Anne L. Bruder, Friends of the Bryn Mawr College Library, 2010: p. 103. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- 1930 United States Census, Haverford Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania: p. 47, dwelling 434, lines 12-18; April 16, 1930. [↩]

- Ibid, line 18. [↩]

- 1930 United States Census, Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania: p. 7, family 72, dwelling 67, lines 10-14; April 5, 1930. [↩]

- Ibid, lines 10-14. [↩]

- James Wolfinger, “African American Migration.” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Rutgers University, 2013, accessed March 6, 2015. http://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/african-american-migration/. [↩]

- Personal correspondence, February 1, 2015. [↩]

Pingback: Who Are We Forgetting? Silences in Black History at Bryn Mawr | Higher Education for Women: Bryn Mawr and Beyond

Pingback: A Note on Method: Researching “Black Labor at Bryn Mawr” | Black at Bryn Mawr

Great read! My great great grandmother (Lummie Parkinson although it reads Louise in the census) was a servant in Merion Hall. I came across the article as I’m trying to piece together her mysterious life. Thank you for this.

Dear Lauren – we were thrilled to hear from you, and Grace continues to work on the histories of women workers in Bryn Mawr’s early history. Thank you for your comment!

Monica