by Grace Pusey

Bryn Mawr College President Kim Cassidy and students Grace Pusey ’15, Khadijah Seay ’16, and Danielle Cadet ’16 (August 31, 2015). Photo credit: Bryn Mawr College Communications.

At Fall Convocation on Monday, August 31, 2015, President Kim Cassidy announced that the residence hall and cultural center built to replace Perry House — the residence hall and cultural center that African American women fought for and won in 1972 (which later also housed members of Mujeres and BACaSO, campus affinity groups founded by and for Latina, African, and Caribbean students) — has been named the Enid Cook ’31 Center in honor of Enid Appo Cook, the first African American woman to graduate from Bryn Mawr College. After President Cassidy shared this news with an audience of students, staff, and faculty packed into Goodhart Hall, I joined Enid Cook ’31 Center co-presidents Khadijah Seay and Danielle Cadet (both Class of 2016) at the Center’s dedication. President Cassidy made a few remarks explaining why Bryn Mawr had chosen to name the Center after Enid Cook and acknowledged Khadijah and Danielle for their hard work and visionary leadership on the Relaunching Perry House Committee. She also thanked me for the essay I wrote on Enid Cook for the Black at Bryn Mawr project, which proved instrumental to the College’s decision to name the building in her honor.

When the festivities ended, I went home and wrote a heartfelt Facebook post about how meaningful the day had been to me. Monica emailed me the next morning to say that she had been moved by what I wrote and asked if I would feel comfortable blogging it, since we have used this space to toggle back and forth between historical research and reflections on the meaning of that research. I agreed; since then, I have been staring at a blank screen, trying to figure out how to repackage what I wrote then for the readers of this blog. What I shared with my friends on Facebook suddenly seemed embarrassingly sincere. Rather than revising my original post, however, I have decided to share it as it was written. It remains the most candid summary of my feelings about the experience, and I cannot think of a way to suppress the emotion behind it without minimizing how truly significant the dedication ceremony was to me. I wrote:

I feel so lucky, so incredibly privileged, to have had the opportunity to research and tell Enid Cook’s story through the Black at Bryn Mawr project. Even though the only words I had to help me tell her story were words that were written about her, not by her — words that were often patronizing and sometimes cruel — Cook’s brilliance and resilience shone through. Existing narratives about her experience, although obscure, celebrated Cook’s phenomenal accomplishments as a scientist and used her story as a benchmark in a narrative of progress and inclusivity at Bryn Mawr. These narratives all but completely erased the racism Cook faced and omitted the fact that the prejudice to which she was subjected was later used as grounds to deter other African American women from applying to the school. I wanted to write Enid Cook’s story in a way that would do it justice.

Because Black at Bryn Mawr was designed as a public history project, I knew that the story I told about Enid Cook could very well become *the* story of Enid Cook. There were times throughout the spring semester when I felt that the amount of pressure I faced to produce work of a caliber fit for public consumption at all times was overwhelming. One factual inaccuracy, or even just a grammatical error, could jeopardize the credibility of the entire Black at Bryn Mawr project and compromise its mission. Writing Enid Cook’s story was particularly intimidating because it was the first story I published to the blog. Yet I realized that the pressure I felt to get her story right was only a fraction of the pressure that Enid Cook experienced constantly, and that many other students of color still feel today — that she and her work were always visible, always vulnerable. Therefore it seems appropriate that her name now graces the space that has historically served as both a refuge for women of color on campus and as a locus of leadership, courage, creativity, and change.

I am touched that Enid Cook’s story has moved others as deeply as it moved me. I never imagined that six months after I published her story to the Black at Bryn Mawr blog I would be looking up at Enid Cook’s name on a campus building, the first building on Bryn Mawr’s campus to be named after a woman of color. Her story is now a permanent part of Bryn Mawr’s landscape. For women of color, Enid Cook’s story resonates and emboldens; for white women like me, her story reminds us that we must be vigilant in confronting ignorance and injustice.

I believe in the power of history to transform culture, and now I have an edifice that I can point to which proves it. I couldn’t ask for better company than Emma Kioko ’15 and Monica Mercado on this journey. I’m especially grateful to Emma for her research on the history of Perry House and for sifting through the “Students — Negro” folder in the Marion Park papers with me at Special Collections back in February, where Enid Cook’s story still resides. The Black at Bryn Mawr project has truly changed my life, and I feel blessed to be part of it. I am comforted by knowing that even after I leave Bryn Mawr “for real” (i.e., when I stop working on the Black at Bryn Mawr project), the project’s work will live on through the story of Enid Cook.

When I say that Black at Bryn Mawr changed my life, I mean it. It has allowed me to hone my research, writing, and public speaking skills. It has permitted me the flexibility to experiment with different writing styles and test drive my pedagogical philosophy. It has connected me to incredible people I would not otherwise have known and allowed me to push the limits of what I thought I could do with a History degree. Thanks to these experiences, I graduated from the College in May with a mission: to pursue a Ph.D. in History and dedicate my life to transformative culture-work as an educator and public historian.

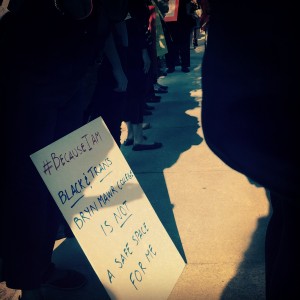

Black at Bryn Mawr has also deepened my appreciation for a Pensby Center mantra often used as a discussion guideline in the College’s diversity education programming: “Trust that dialogue can bring us to deeper levels of understanding.” The Black at Bryn Mawr project has been but one piece of a larger, ongoing community conversation at Bryn Mawr sparked by an incident in which two students hung a Confederate flag in Radnor Hall in September 2014. Rather than targeting Black at Bryn Mawr‘s critique at the flag or the two students who displayed it, however, Emma and I employed a Baudrillardian approach: in tandem with the stated goals of the campus-wide demonstration that took place in late September 2014, we set out to show that the real “scandal” was not the flag or the students who displayed it, but Bryn Mawr’s long legacy of unsafety for marginalized groups. In this way, Black at Bryn Mawr demonstrated how student scholarship can buttress and sustain student activism.

In an October 1993 interview with Donna Landry and Gerald Maclean, Gayatri Spivak spoke about the importance of recognizing our own positionality in relationship to our scholarship and examining our own racism. “I’m of course, with every bit of my conscious thinking, every bit of my work, in all of my interventions, strongly, fundamentally, and in every way anti-racist,” she said, “but history is larger than personal goodwill. Therefore I think we must confront the possibility that in what we produce there may be residual elements [of racism] that can give fuel to the other side.”1 Black at Bryn Mawr gave me the chance to deepen my own awareness of racial power dynamics on campus and to share that understanding with others through historical scholarship. But on a more immediate level, it also pointed my attention to the ways in which I have, as a white woman, often imperfectly navigated classroom space as well as spaces outside the classroom as a listening and speaking subject. This has allowed me to reexamine and reframe my interactions with my fellow community members as part of what I “produce” — to borrow Spivak’s term — as a scholarly agent. What I came to understand through Black at Bryn Mawr was that, whether we are conscious of it or actively assume responsibility for it or not, we are all implicated in creating a safe and supportive learning environment for one another.

Ultimately, the purpose of the project is not to condemn the two students who hung the Confederate flag, but to draw attention to the importance of changing the relationships we have with one another and to the salience of truly valuing the educational process not just for ourselves, but for everyone around us. As college-educated people, we are in a uniquely privileged position to help shape public conversation and debate at local, national, and even international levels. For precisely this reason, I think it is important for white students in particular to pay attention to how we are supporting students of color at Bryn Mawr and making space for their perspectives and contributions both inside and outside the classroom. It is my hope that the Enid Cook ’31 Center will serve as a permanent reminder to do this.

Suggested Reading:

Bryn Mawr College Names New Residential Space in Honor of School’s First African-American Alumna, Bryn Mawr College News, August 31, 2015.

Grace Pusey, Enid Cook, 1927-1931: Bryn Mawr’s First Black Graduate, February 2015.

Emma Kioko, “Unwavering Dissent” Part I & Part II, March-April 2015.

Danielle Cadet and Khadijah Seay, The Official #ProjectPerry Website.

Grace Pusey, Grace’s Reflections on Black at Bryn Mawr, April 2015.

- Gayatri Spivak, “Subaltern Talk: Interview with the Editors,” The Spivak Reader (eds. Donna Landry and Gerald Maclean), 29 October 1993, p. 297. [↩]