by Grace Pusey

Most of the blog posts that Emma and I wrote during the spring semester spotlighted our research findings, but not necessarily our research methodology or any of the other cool or interesting things we did related to the project. Monica Mercado, who is supervising my continued work on the Black at Bryn Mawr project, suggested I share these sorts of things on the blog as I move the project forward with a grant I secured for the summer. From now on you can find posts like this under the “Methodology” tab in the navigation bar. So far I have been busy giving tours, presenting at conferences, following up on research leads, arranging times to visit archives and historical sites, and reading, reading, reading. I hope sharing my experiences will interest you!

Yesterday I went to City Hall in Philadelphia to check out Monument Lab, a public art and urban research project guided by the question, What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia? Every day throughout the month of May and the first week in June, Philadelphians can stop by Monument Lab research pavilion at City Hall to see a series of art installations, partake in public events, enjoy the prototype monument by artist Terry Adkins, or listen to free dialogues led by Philadelphia artists and intellectuals. Visitors can sit at the picnic tables in front of the research pavilion to craft their own proposals for monuments, which are then mapped digitally and displayed online.

Monument Lab: Creative Speculations for Philadelphia. Major support for Monument Lab was provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage with partners including Penn Institute for Urban Research, City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program, Haverford College, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, PennDesign, the Philadelphia Center for Architecture, and RAIR.

Monument Lab is an innovative project aimed at engaging people in dialogue about Philadelphia and what about the city matters to them. What about Philadelphia is important to Philadelphians? What is currently invisible that we want to make visible? Why are monuments important, and how do we use them to intervene in spatial narratives — the stories we tell about space?

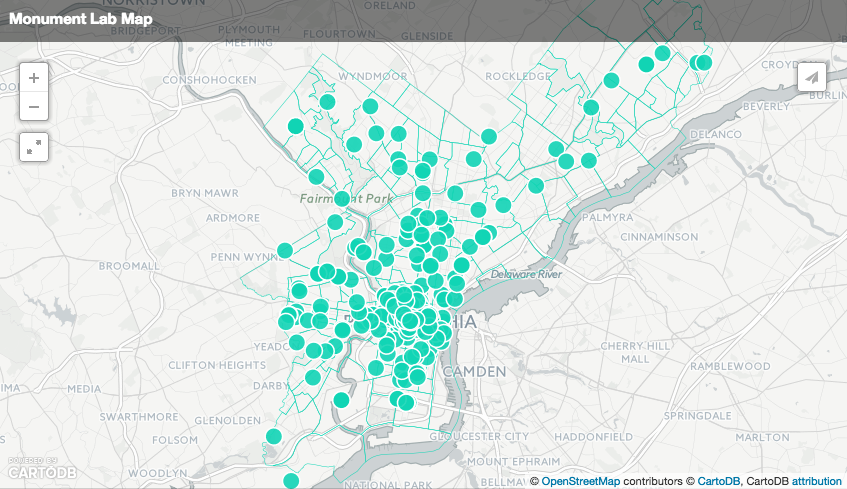

City Hall is located in the heart of Philadelphia, at the center of a heavily monumentalized landscape. At “Their Story, Our Story: The Gay Pride Movement,” a lecture at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania I attended on Wednesday night, I learned that Reminder Days — the predecessor to Gay Pride parades — were originally staged at City Hall because organizers felt the site’s association with American history and government would lend import to their cause. Interestingly, the majority of the 350+ monument proposals submitted by Monument Lab participants were for monuments at City Hall and its surrounding localities. Out of curiosity I looked at the proposal map to see if anyone had suggested monuments for the West Philly neighborhood where I currently live or the North Philly neighborhood where I used to live. I found that the further away I panned from 15th and Market Streets, the fewer monuments were proposed; there was only one proposal for my old neighborhood and two proposals for my current neighborhood. This made me think about the kinds of stories that get told about the places we live, and particularly about how some parts of the city are treated as less important and more disposable than others. If Monument Lab had moved its research pavilion to different parts of the city throughout the month, would the map of proposed monuments look different? Or would people still assign a disproportionate amount of significance to the landscape around City Hall?

Map of proposed monuments, June 4, 2015. (Map created by Haverford Digital Scholarship, Haverford College, PA.)

Philadelphia is known as the “mural capital of the world,” and there are numerous murals on my block. There is a mural that reads “Miss you too often not to love you,” which I photographed and sent to a friend when they went away on a trip last fall. There is a mural in memoriam of a man who died too young painted by his friends and family. There is a mural on the side of the local elementary school and on a wall behind the nearby children’s play park. There is even a mural commemorating local Philadelphians lost on 9/11. Murals are everywhere. Murals infuse the landscape with color, life, memory, and even wisdom, as inspirational quotes from great American leaders scattered throughout the city attest.

The photograph of a mural I sent to a friend. | Steve Powers, “A Love Letter for You,” sponsored by the Mural Arts Program, Philadelphia, PA.

Monuments can come in many forms, and murals are certainly a type of monument. One of the questions that Monica (who accompanied me to the noon talk I attended) asked was: What is a monument? Is a monument always static, or can it be moving? Could the Black at Bryn Mawr walking tour be considered a kind of monument to Bryn Mawr’s Black history?

It’s an interesting question. On Wednesday while I was giving a tour to the Bi-Co Dalun Fellows, Professor Alice Lesnick pulled up an email on her phone to tell me that Enid Cook, Bryn Mawr’s first African American graduate, was one of the top three finalists for the renaming of Perry House. If chosen, her name could become the new legacy-bearer of the first Black Cultural Center on campus and take on lasting significance in the Bryn Mawr community. One of the questions people ask frequently on tours is whether or not we plan to mount plaques around campus explaining how different sites are tied to Black history. I think the walking tour functions a little differently than how I imagine a monument functions traditionally; as one alumna put it succinctly during the Alumnae Reunion Weekend tour, “It can be hard to make people sit down and have a conversation, but if you create an experience for them, conversation will flow.” Monuments don’t necessarily create an experience or even prompt conversation, but become fixtures of the landscape and therefore embedded in the identity of a place. And maybe that’s exactly what Bryn Mawr needs: for the historical contributions of Black community members to become fixed features of the campus landscape, to be made permanently visible.

Personally I’d like to see a mural depicting Enid Cook with a microscope or a chemistry set in Park Science. What do you think?