by Grace Pusey

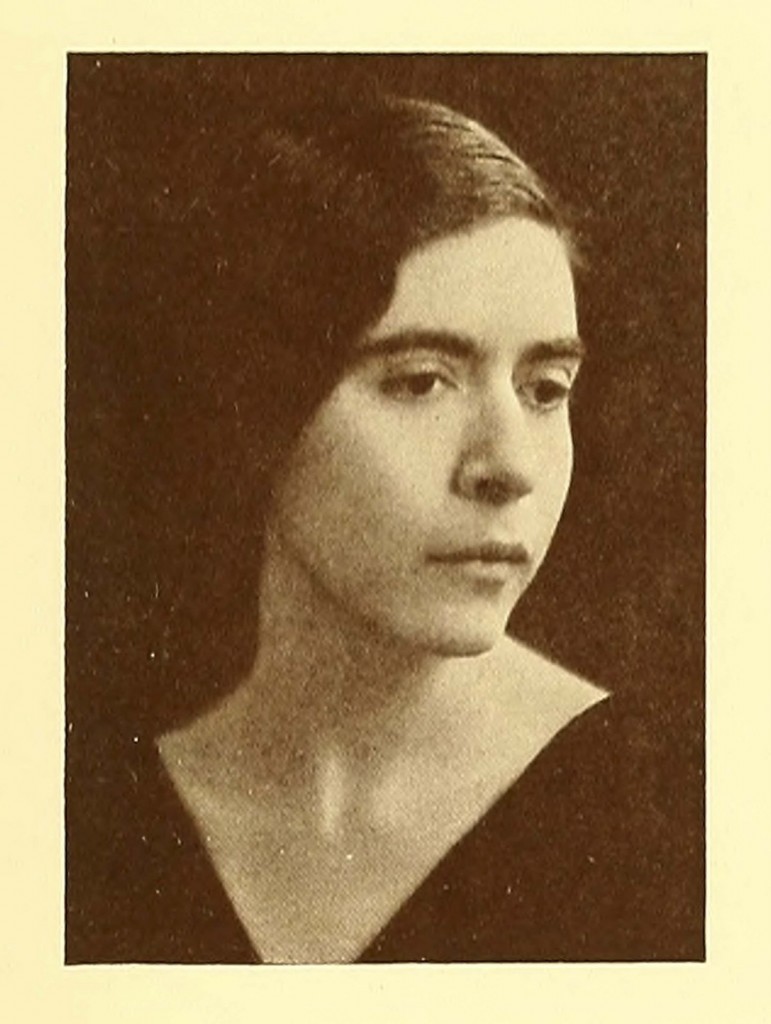

Emma and I commenced our research on Black history at Bryn Mawr with a file labeled “Park Students – Negro” in a box of papers pertaining to Marion Park’s presidency housed at Bryn Mawr College Special Collections in Canaday Library. Marion Park was President of the College from 1922-1942, and though her administration was not the first to handle the “question” of Black students’ admittance to Bryn Mawr, it was the first to craft admissions policies that set a precedent for the admission of Black students to Bryn Mawr as non-residents.

In response to a compromise proposed by President Park that Black students could attend Bryn Mawr, but only if they lived off campus, M. Carey Thomas (who served as the College’s second President from 1894-1922 and remained an influential College voice after her retirement) wrote a letter to Park dated September 7, 1926 expressing her support. After all, she opined, permitting Black students to live in residence alongside white students would “[…] outrage the social conventions to which [white students] and their families are accustomed,” and such a policy could not be carried out “[…] without arousing deep resentment, and, as a consequence, losing much loyalty, financial support, and very many highly desirable white students from our home state of Pennsylvania, New York, and other Middle Atlantic states, and practically all our Southern students.” Moreover, Thomas insisted that “[…] there seems to be little, if any, appreciable movement toward the admission of negroes into our social life […]. On the contrary, I believe, that the result of the scientific studies of the effects of immigration and of the teachings of heredity now being made are leading us in the other direction.”

In other words, Thomas believed that modeling social reform was less vital to the College’s mission than securing financial backing bequeathed to the institution by white students and families who relied on Bryn Mawr’s reputation to bolster and perpetuate their elite status in white society, especially given that “scientific studies of the effects of immigration and of the teachings of heredity” engendered doubt that social reform would prove necessary or valid at all in the long term. Admitting Black students to Bryn Mawr as non-residents only would appease advocates of social reform, at least temporarily, while minimizing the risk of alienating Bryn Mawr’s key financial constituents.

The non-residency stipulation for Black students’ admission was a noncommittal answer to the question of whether or not Black women should be entitled to the same educational and social opportunities as white women. To the question of social opportunities, Bryn Mawr’s response was a firm “no.” Black students’ exclusion from campus life was designed to prevent them from socializing with white students as much as possible, and preferably not at all. To the question of educational opportunities, Bryn Mawr extended a reluctant “yes” that could be — and in fact, later was — rescinded gradually without reneging on established precedent by manipulating the rules and regulations imposed on students residing off campus. (Emma and I will elaborate on this in forthcoming posts.)

The letter from M. Carey Thomas to Marion Park demonstrates that, even with the implementation of reforms that permitted Black students to earn degrees from Bryn Mawr for the first time in the College’s history, the administration’s prerogative was not progress, but appeasement.

A scanned copy of the letter and a typed transcription after the jump. Continue reading →