by Grace Pusey

My sketch in response to the “Backtalk” exhibit at Bryn Mawr College, February 21, 2015.

On Saturday, February 21, 2015 I attended the Creative Workshop engaging the Backtalk: Exposures, Erasures, and Elisions of the Bryn Mawr College African Art Collection exhibit in Canaday Library. The workshop, facilitated by Whitney Lopez, Class of 2015 and Alice Lesnick, Term Professor of Education and Africana Studies Coordinator, encouraged students to respond to the exhibit via writing, visual media, and performance. The exhibit itself showcases 35 artworks pertaining to various aspects of family, political, and spiritual life and invites viewers to “[…] engage questions of what the collection includes, leaves out, clarifies, and obscures, as well as how the collection came to be and how it functions within and beyond the College.”1 Because creativity is not my forte I was hesitant to participate in the workshop, but I forced myself to go for two reasons. First, I felt strongly that the questions the exhibit poses about Euro-American legacies of colonialism in Africa and Bryn Mawr’s relationship to them were relevant to the Black at Bryn Mawr project. Second, I felt it would be terribly opaque to focus solely on the “hidden histories” of Black experiences at the College revealed to us in archived documents while overlooking spaces on campus where Black students, faculty, staff, and their allies are already questioning Bryn Mawr’s representation of its history, challenging its master narratives, and speaking truth to power.

“Backtalk” exhibition on view through May 2015 at Special Collections. Photo via Friends of the Bryn Mawr College Libraries.

Whitney and Professor Lesnick opened the workshop by giving us some background information about the exhibit, including the collection’s history as well as the inspiration for the exhibit’s format. I learned that there are 364 items in the College’s African Art Collection, and that the last time any of them were displayed was in 2000. Over 250 items were donated by Helen Katz Neufeld (Class of 1953), and her husband Mace Neufeld, a veteran TV and film producer.2 More than thirty items were bequeathed to the College in 1990 by Margaret Plass, who developed a passion for collecting African art along with her husband Webster Plass, a petroleum company engineer, when they were stationed in the Belgian Congo by the U.S. Navy. Plass’ obituary states that she graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1917, but this is not, in fact, true.3 In an archived interview with Plass from 1982, shortly before her death in 1990, Plass explained that she was a student at Bryn Mawr from 1913-1915 but “flunked out” because a “little cultery [sic] of lesbians” in the English Department conspired to have her expelled.4 Nonetheless, the College hired her to teach a series of lectures on African art in 1962.5 Most of the items in the Collection do not have an artist’s name listed and are instead credited to Neufeld and Plass, their collectors, or to the country or ethnic group from whence the object originated. (For example, multiple items have “Uganda” listed as both “artist” and “place of origin.”) It seems unlikely that Neufeld and Plass did not have access to artists’ names; rather, both collectors deemed such information unimportant.

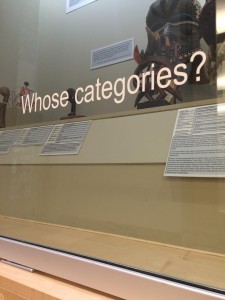

“Backtalk” encourages viewers to interrogate the ways in which institutional and collecting practices (like Neufeld and Plass’ decision to not credit the original artists) shape, transform, and even mutilate the meanings and identities of collected objects. A plaque next to Neufeld and Plass’ biographies asks, “What roles do collections and institutions play in the identity of each object? What should these roles look like?”6 The explicit inclusion of “question marks” in the exhibit’s design is inspired by Fred Wilson’s exhibit “Mining the Museum” at the Maryland Historical Society. According to one of the plaques at the “Backtalk” exhibit,

“By titling his installation ‘Mining the Museum,’ [artist Fred Wilson] set up a three-way pun: excavating the collections to extract the buried presence of racial minorities, planting emotionally explosive historical material to raise consciousness and effect institutional change, and finding reflections of himself within the museum. ‘Oú est mon visage?’, reads Wilson’s label accompanying Joshua Johnson’s 19th-century portrait of a white family. An artist of African and Carib Indian ancestry, Wilson identified with Johnson, who was black, and of whom there are no known portraits.”7

In this way, “Backtalk,” like “Mining the Museum,” seeks to center the experiences and perspectives of the peoples and cultures to whom the items are indigenous while unsettling the assumptions and practices of museum collectors and consumers alike. Some of the questions included, What is valued? Once sacred, always sacred? Where does “object” end and “context” begin? Does this exhibition have a cost? Whose collection? Whose knowledge? Whose language? Whose categories? What is preserved and what is lost?

What is valued? Once sacred, always sacred? Where does “object” end and “context” begin? Does this exhibition have a cost? Whose collection? Whose knowledge? Whose language? Whose categories? What is preserved and what is lost?

For our first activity, we were supposed to choose an object and sketch a response to it. I had a difficult time choosing just one object, so I sketched a response to the entire display. On the lefthand side of my sketch I drew a memory from my childhood. Once when I was in primary school I picked a bouquet of wildflowers for my mom. Rather than being happy, however, my mom was upset. She explained that I had no right to pick the flowers, that they didn’t belong to me, and that I had cut their lives short. My mother wasn’t a hippie, and I never once heard her use the word “environmentalist” to describe herself, but she had been taught by her mother, who had learned from her mother, who had learned from her mother, and so on and so forth, that the only way to appreciate nature is to respect it. In contrast, I was taught a very different message about the world in school: I was never taught to challenge dominant Euro-American cultural narratives enshrined and perpetuated in museum displays about ownership and access to other peoples’ cultures and histories. My mother signed permission slips for field trips to museums and never questioned their institutional role in public (mis)education, nor their colonial legacies. So, next to my sketch of my mother rejecting my bouquet of flowers, I sketched a class field trip to a museum, with a teacher gesturing to a floral display (a metaphorical nod to the bouquet in the adjacent sketch) instead of replicating the objects in the case before me.

In retrospect, my symbolic choice of flowers was apt. The concept of indigeneity, at least in a Western context, arose in early modern Europe amongst botanists, apothecaries, and natural scientists to defend the utility of local plants and medicines against the influx of foreign ones from royally sponsored expeditions abroad.8 They believed God blessed all people with the natural resources they needed to survive, and that to seek resources beyond those immediately available to them was tantamount to questioning God’s providence. Moreover, curio cabinets — the forerunner to museum display cases — were created originally to display natural objects, but came to house “curiosities” (hence “curio”) as commissioned privateers returned from voyages with souvenirs from their cross-cultural encounters. Though the concept of indigeneity now evokes a very different milieu of meanings,9 it remains relevant to the African Art Collection at Bryn Mawr, and to collections of items belonging to colonized peoples in museums everywhere: how can curators and viewers alike work to decenter the people and institutions that colonized the objects’ original owners and recenter the indigenous voices and experiences of the people and cultures to whom the objects originally belonged (and ostensibly, still belong)?

Short of repatriating the items in the African Art Collection, “Backtalk” is an important step in the right direction. It acknowledges that an injustice has been done and invites the College community to take collective responsibility for redressing these historical wrongs. During our final reflection activity, Whitney pushed us to think about next steps: Where do we go from here? How do we respect the students whom this exhibit, and the African Art Collection more broadly, represents? How do we support the voices of African and Afro-descendent students on campus? How can this exhibit lead to positive and sustainable change — for the Collection, for students, and for inhabitants of the African continent?

What I appreciated most about the creative workshop was that we were able to take a serious topic and explore it through play. In addition to sketching, we also created “human sculptures” in response to objects in the Collection, and some of us (well, everyone but me) wrote poetry (which, I might add, was amazingly good! And I say this as someone who is difficult to please.) There were moments — particularly after we first looked through the exhibit thoroughly, but throughout the workshop, too — when we experienced strong emotions, but these were respected and used to guide the discussion. It reminded me that there of many ways of knowing and many ways of coming-to-know, and that thinking outside the box can take us in exciting new directions, open space for new questions, and allow us to extend, elaborate, and expand upon information presented to us in unexpected ways.

You can engage “Backtalk,” too!

What: Panel Discussion

When: Wednesday, February 25, 6:00 p.m. — 8:00 p.m.

Where: Canaday Library 2nd Floor Coombe Suite

Kalala Ngalamulume, Associate Professor of Africana Studies and History; Linda-Susan Beard, Associate Professor of English, BMC; Alicia Walker, Assistant Professor of Medieval Art and Architecture; and moderator Whitney Lopez ’15 will discuss evolving methods for talking back, with attention to the tensions and synergies between scholarly and political discourse.

You can also view “Backtalk” in the Second Floor Gallery and First Floor Lobby, Canaday Library, February – May, 2015.

- Museum label for “About the Backtalk Exhibit,” Bryn Mawr, PA, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, February 21, 2015. [↩]

- Museum label for Mace Neufeld (b. 1928) and Helen Katz Neufeld (1931-1995), Class of 1953, Bryn Mawr, PA, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, February 21, 2015. [↩]

- Doreen Carvajal, “Margaret F. Plass, Globetrotting Art Lover,” February 12, 1990, philly.com, accessed February 23, 2015, http://articles.philly.com/1990-02-12/news/25881583_1_african-art-collections-british-museum. [↩]

- Interview with Margaret Plass, 1982, Margaret Plass Papers 1886-1990, Box 1 of 4, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA: p. 36. [↩]

- Museum label for Margaret Feurer Plass (1886-1990), Class of 1917, Bryn Mawr, PA, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, February 21, 2015. [↩]

- Museum label for “Donor Portrait,” Bryn Mawr, PA, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, February 21, 2015. [↩]

- Quote from Judith Stein, “Sins of Omission,” Art in America, October 1993. Museum label, Bryn Mawr, PA, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, February 21, 2015. [↩]

- Alix Cooper, Inventing the Indigenous: Local Knowledge and Natural History in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.) [↩]

- That the concept of indigeneity is no longer associated with natural history is not disconnected from the aforementioned observations. Early modern European defenses of indigeneity included the claim that people and their environments were designed to be a “perfect fit.” This claim was appropriated for the British Crown by natural philosopher Robert Boyle, who penned General Heads for a Natural History of a Countrey, Great or Small for the Royal Society in London in 1668. Seafarers, Boyle instructed, were to provide information about the appearance, diet, and customs of Native peoples, their labor and agricultural methods, as well as any diseases or contagious illnesses that plagued their communities. This information served the Crown in several important ways. It told the monarchy what, if anything, of value could be gained from future expeditions to the New World. It told sailors whom they could expect to meet and how to maximize their interactions with Indians. Additionally, and more abstractly, it bolstered England’s claims to imperial power by facilitating the flow of information to the Crown, advancing England’s aspiration to be the most erudite monarchy in the world. That the pursuit and possession of knowledge could be an imperial act distinguished the English conception of empire from that of its Catholic archenemy, Spain. Arthur Williamson has described early modern British expansion under Queen Elizabeth’s reign as an attempt to create an “empire to end all empire,” and has argued convincingly that despite England’s dearth of material wealth in comparison to Spain, the Protestant Crown asserted its moral superiority by envisioning an alternative form of empire that would liberate people, not oppress them. Of course, the historical record reveals that England fell far short of this vision — evidence abounds that England committed the same kinds of atrocities for which it once feared and condemned Spain. (See Arthur Williamson, “An Empire to End Empire: The Dynamic of Early Modern British Expansion,” Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 68, No. 1/2, The Uses of History in Early Modern England (2005), pp. 227-256. Thanks to Associate Professor of History Ignacio Gallup-Diaz for weaving the General Heads and Williamson readings into the Spring 2014 curriculum for his 300-level History course “Early Modern Pirates.” [↩]