by Grace Pusey

Content Warning: This post contains racist slurs.

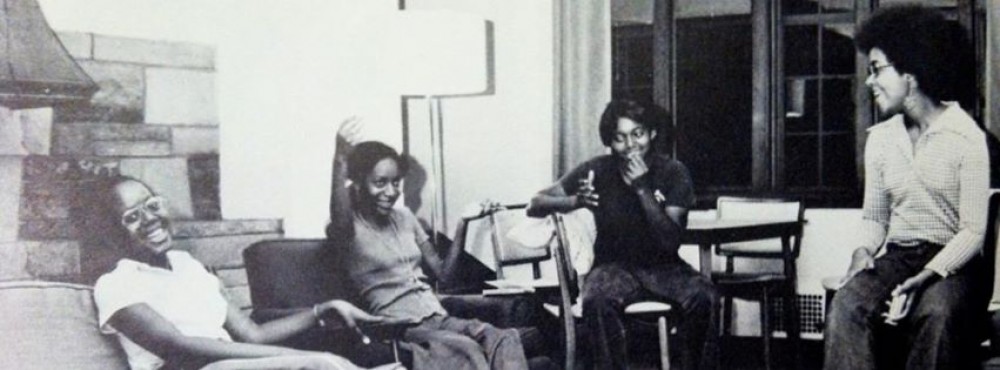

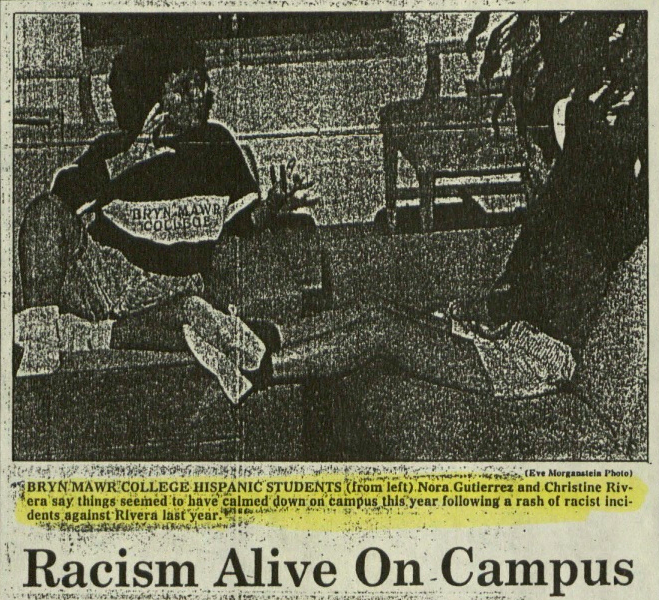

“Bryn Mawr College Hispanic students (from left) Nora Gutierrez and Christine Rivera say things seemed to have calmed down on campus this year following a rash of racist incidents against Rivera last year.” Diane Garrett, “Racism Alive on Campus,” Main Line Sunday, Vol. 6, No. 36, October 22, 1989. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

ON OCTOBER 7, 1988, first-year student Christine Rivera returned to her dormitory to find an anonymous note slipped under her door. “Hey, spic,” it read, “Why don’t you leave Bryn Mawr? If you and your kind can’t handle the work here, don’t blame it on this racial thing. You’re making our school look bad to everyone else. If you can’t handle it, get out. We’d all be a lot happier.”1

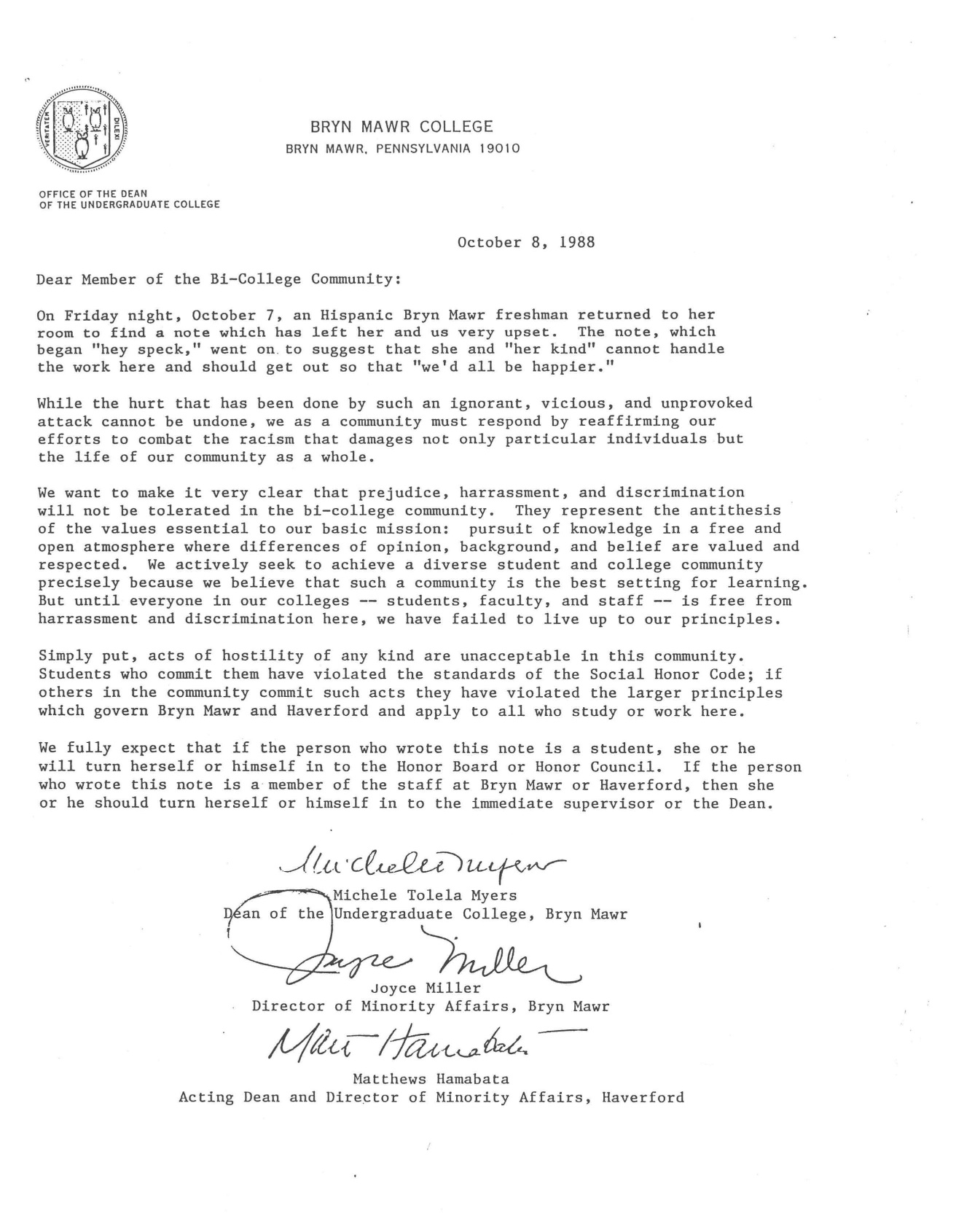

Rivera reported the note immediately. College administration responded swiftly, issuing a memo to students, staff, and faculty the next day. “We want to make it very clear that prejudice, harassment, and discrimination will not be tolerated in the bi-college community,” it read. “They represent the antithesis of the values essential to our basic mission: pursuit of knowledge in a free and open atmosphere where differences of opinion, background, and belief are valued and respected. […] [Until] everyone in our colleges — students, faculty, and staff — is free from harassment and discrimination here, we have failed to live up to our principles.”2 The memo concluded by urging the perpetrator of Rivera’s harassment to turn herself in to the Honor Board, or to his or her immediate supervisor if they were College staff.

No one came forward, however, and the abuse continued. First, Rivera found a paper she had written for an English course slipped under her door with a slash through her last name. Then she discovered a decoration that she had hung on her door ripped to shreds and slipped underneath it. “I was very fearful of walking through my door,” Rivera later admitted in an article published in Main Line Sunday a year after the initial verbal attack,but she did not report these incidents at first.3 Unwittingly placed at the center of an unfolding campus scandal, she “[…] didn’t want to cause any more tension.”4 Because the identity of Rivera’s harasser remained unknown, all the controversy was drawn to her. Some students, unable to fathom how such a vitriolic note could have been written by anyone at an institution with a “liberal, open-minded” reputation like Bryn Mawr’s, even believed Rivera was faking her own harassment.

“People didn’t want to believe that an aesthetically beautiful place like Bryn Mawr could have this happen,” said Nora Gutierrez, one of Rivera’s closest confidantes.5 Mei Cal, a Haverford student, agreed. “People were shocked that it happened at Bryn Mawr,” she said, “but it was not a shock to me.”6 Peter Anderson, who befriended Rivera during the Tri-College Summer Institute (a leadership intensive for first-year students of color), felt students’ suspicion that Rivera had feigned her abuse was “ludicrous.” Speaking from personal experience, Anderson said that Black male students at Haverford were often asked for ID or presumed to be support staff. “It’s very hard for people to believe there are male black students who are as smart and competent as anyone,” he said.7 In other words, for students of color in the Bi-College community, racism was simply a fact of life. The overtly racist verbal attack against Rivera may have been extreme, but it was not inconceivable given the subtle, pervasive forms of racism that students of color experienced daily on Bryn Mawr and Haverford’s campuses.

Memo from Deans to the Bi-College Community, October 8, 1988. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

A Long Time Coming: Institutional Attempts at Change

Indeed, the anonymous note arrived in the midst of institutional awakening to the racism students of color faced. At Bryn Mawr, students of color comprised 19 percent of the total student body of 1,202. Three were American Indian, forty-nine were Black, thirty-six were Latina, and 143 were Asian American. An additional 10 percent were international students from countries as diverse as Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, and Kuwait.8 Despite having a more diverse student body than most other elite institutions at the time, students of color did not feel welcome on campus. Graduation rates were lower for students of color than for their white peers; for example, only 56 percent of Black students graduated from Bryn Mawr within four years. Moreover, at a school which consistently graduated approximately 1,000 students annually, the College graduated fewer than one hundred Black students in the near century between Bryn Mawr’s founding (1885) and 1980.9 “If you are willing to play the game and conform to white male standards, then people [treat you] well,” explained Denise Tuggle, a senior Black student from Orrington, Maine and leader of the Minority Student Coalition on campus. “If you’re not willing to play the game, then the environment is fairly hostile.”10 Institutional reforms had been in the works for several years, but racial tensions at Bryn Mawr exploded in 1988-1989, with Rivera’s harassment at the epicenter of it all. Galvanized by Rivera’s experience, students made increasingly assertive demands for change. Chronologically, the progression of events between 1988-1989 is thus:11

Spring 1988: The spring before Rivera matriculated to Bryn Mawr, the Bryn Mawr Minority Coalition printed a petition in the College News calling for mobilization against racism and classism in course curricula. The petition, signed by more than 400 students and several faculty members, came on the heels of a decision made by College administration in 1987 to not hire new faculty for courses on the histories of marginalized groups, but to incorporate histories of women of color into existing courses instead. Despite the installation of guidelines for diversifying course curricula, many students felt professors had failed to demonstrate commitment to implementing those guidelines in their syllabi, and in April 1988 they marched silently through the campus to protest the lack of repercussions for faculty who made little or no effort to adhere to the principles outlined.

Furthermore, on April 8, 1988, a list of the Minority Coalition’s demands were printed in the College News. These demands included hiring more faculty of color, increased pay for Bryn Mawr’s majority Black housekeeping and food service staff, and seminars to increase sensitivity to issues of racism and classism on campus. In response, the College secured a $200,000 Pew Charitable Trusts grant to implement diversity training workshops in the fall.

September 1988: Mandatory pluralism workshops were conducted for all dorm presidents, hall advisors, student government leaders, and first-year students. Juniors and seniors’ participation was optional, but many elected to attend; in total, seven hundred students took part. Staff and faculty were not required to receive diversity training, but many did participate, as did most College trustees.

October 1988: In the same month that Rivera received her first anonymous note, faculty received notes from students expressing deep disappointment at their lack of response to diversifying the curriculum. The Bryn Mawr Minority Coalition also sponsored a forum in response to the racist note received by Rivera. Approximately 250 students attended, of whom the majority were other students of color.

November 1988: In early November the Honor Board sponsored a forum titled “Racism and the Honor Code,” which was described in the College News as “tense and emotional.” On November 13 the Minority Coalition hosted a forum to form specific plans to combat harassment on campus. The next day, November 14, bathrooms in Thomas Great Hall and Campus Center were found covered in graffiti. There was graffiti affirming all marginalized groups on campus in response to bigoted graffiti targeting Jewish, lesbian, and Latina students. On November 16, President McPherson and several deans repainted the bathrooms late at night, stating, “Graffiti is not the way to have a dialogue in this community.”

January 1989: The Self Government Association held plenary on January 20. A new, more general Honor Code was passed with an amendment stipulating that “acts of prejudice” violated the Code. The amendment, still in force today, now reads:

We recognize that acts of discrimination and harassment, including, but not limited to, acts of racism, homophobia, classism, ableism, and discrimination against religious and political minorities are devoid of respect and therefore, by definition, violate this Code.

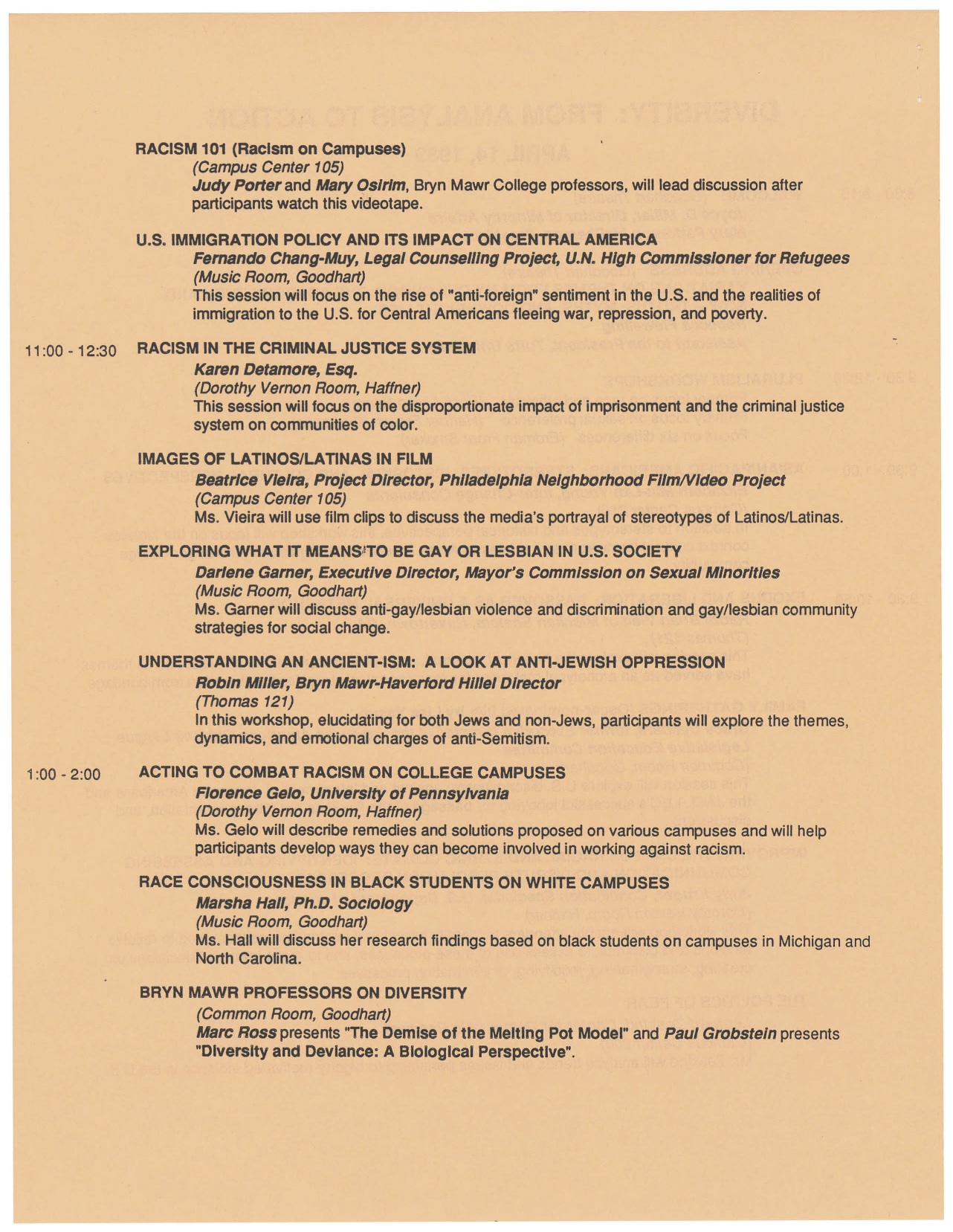

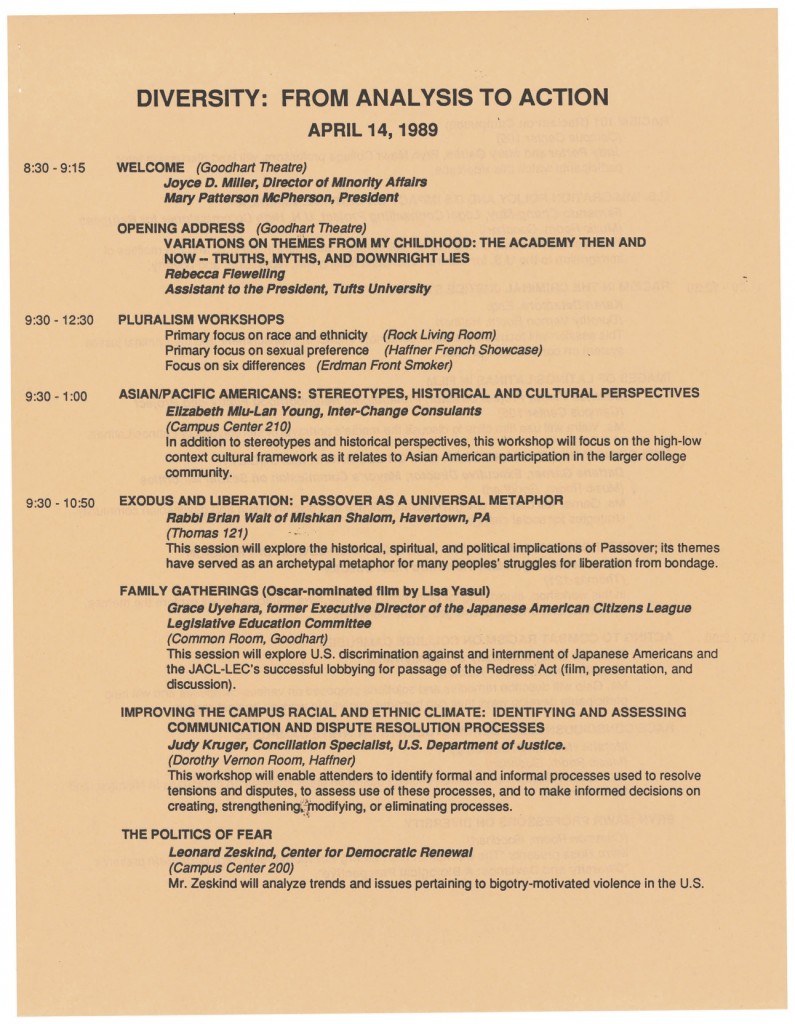

April 14, 1989: Recognizing a need for serious community dialogue between students, staff, and faculty, the College held an event in April 1989 structured almost exactly like the recent Community Day of Learning on March 18, 2015. The event, titled “Diversity: From Analysis to Action,” featured workshops on race, ethnicity, sexuality, religion, ability, power and privilege from 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM and concluded with dinner al fresco on Erdman Green, followed by a concert in Goodhart Hall.

In short, among the reforms that took place between the fall of 1988 and spring of 1989 were mandatory diversity training for students, diversification of course curricula, and the addition of a “diversity clause” to the Honor Code which empowered students of color and other marginalized groups with the ability to seek redress for discriminatory acts. Interestingly, a review of the chronology of events between 1988-1989 reveals a pattern: attempts at dialogue were often followed by either institutional silence (prompting, for example, students to march silently through the campus to protest faculty inaction in response to demands for diversification of curricula) or by reactionary attacks by renegade community members (e.g., the anti-Semitic, homophobic, and racist graffiti in Thomas Great Hall and Campus Center which appeared the day after the Minority Coalition hosted a forum to form specific plans to combat harassment on campus.) Rivera’s experience was no exception to this pattern. In April 1989, she came forward and confessed she had received more racist notes since October, which had become progressively more threatening in the six month interim.

“Diversity: From Analysis to Action,” April 14, 1989. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

First-Year Continues to Receive Racist Notes

The harassment escalated during Rivera’s second semester at Bryn Mawr. She continued to receive anonymous notes, which became progressively more aggressive and threatening over the course of the term. They insinuated Rivera would be injured — or worse — if she failed to comply with her harasser’s demands. “You’re making a big deal out of this racial thing,” one said. “Is that because you can’t do the work?” “Obviously you need more incentive to leave,” said another. “If you don’t, something bad is going to happen to you.”12 Rivera finally broke her silence when she received a note calling her (white) boyfriend a “traitor.” “I thought, ‘I shouldn’t be dealing with this,’” she said.13 Recognizing that not only her safety, but the safety of her friends and loved ones may be at stake, she reported the notes to Lower Merion police.

The College moved Rivera to another dormitory and gave her extra security protection. An investigation was conducted, but when no culprit was found the College terminated Rivera’s security detail. Fortunately the harassment ceased after Rivera relocated, but she was left with “anger at a person who would do that and a community who would harbor such a person.”14 Rivera found it hard to believe that no one knew or had any idea who left the anonymous notes. Joyce Miller, Bryn Mawr’s Director of Minority Affairs, sympathized with Rivera’s discontent. “If I were Christine, knowing the person was never caught, I would feel not enough was done,” she said. “I think that we [Miller and other College administrators] will never have a meeting of the minds on that.”15

Despite all that happened, Rivera returned to Bryn Mawr for her sophomore year. The administration, however, was less willing to have her return. They asked Rivera to take a year off due to her poor academic performance in several courses. Rivera refused. “Granted, I did fail courses,” she said, “but it was my standpoint [that] I had every right to come back.”16 Rivera, who grew up in suburban Los Angeles, came to Bryn Mawr with a mission and was not easily deterred. Despite her mother’s misgivings about sending her daughter to a place where people would “look at [her] and notice,” Rivera wanted to prove that Latina students could succeed at a predominantly white, elite academic institution like Bryn Mawr. Rivera’s friend Nora Gutierrez said her determination inspired other students of color at Bryn Mawr: “[They] all look at her with awe.”17

Allegra Tomassa Massaro, Class of 2015, holds sign that reads, “Administrators: Silence Speaks Volumes.” To her left are fellow students Michelle Lee and Olivia Porte. Photo Credit: Michael Bryant, Staff Photographer for the Philadelphia Inquirer. From Susan Snyder, “Confederate Flag in Dorm Roils Bryn Mawr Campus,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 6, 2014.

Where Are We Going, Where Have We Been?

In September 2014, two seniors hung a Confederate flag in Radnor Hall and taped a “Mason-Dixon line” on the floor outside their door. When student leaders asked the students to take down the flag due to its incendiary associations with slavery, lynchings, and White supremacy, the students moved it to a location where it was visible through a window facing Bryn Mawr’s campus. College administration responded to the event belatedly and provided conflicting advice, leaving many students feeling unsupported. Moreover, a letter of apology addressed to the Bryn Mawr community by the two seniors struck some as insincere and misconceived, communicating regret that their actions had sparked outrage but offering little remorse for their actions themselves. On October 22 Dean Judith Balthazar notified the Bryn Mawr community that the students had been removed from Radnor Hall, but the matter was hardly settled. In the same way that Rivera’s harassment sparked serious community dialogue around racism at Bryn Mawr in 1988, the Confederate flag incident prompted students, staff, and faculty to reflect again on the College’s legacy of unsafety for marginalized groups.

On March 18, 2015 the College held a Community Day of Learning to promote campus-wide dialogue on the benefits and challenges of living and learning in diverse community. Though the exact number of attendees is yet to be revealed, a recent Bryn Mawr College communications bulletin provided an estimate of 1,000. The event, titled “Race and Ethnicity at Bryn Mawr and Beyond,” featured performances, interactive workshops, lectures, and panel discussions facilitated by students, faculty, and staff. “We still have a long way to go,” President Kim Cassidy said of the event, “but today was an important first step and we took it together.”18

Student panelists Faatimah Jafiq, Tara Wadhwani, Maryam Elarbi, Shamial Ahmad, and Alizeh Amer facilitate discussion on “Islamophobia: Faith and Race” at the Community Day of Learning, 2015. “Campus Comes Together for Community Day of Learning,” Bryn Mawr College News Bulletin, March 20, 2015.

But was it really the first step?

Like the Community Day of Learning, the Black at Bryn Mawr project was born out of several community-wide conversations that occurred in the aftermath of the hanging of the Confederate flag. The purpose of the project is to build institutional memory of Bryn Mawr’s engagement with racism, enabling future students to hold both themselves and the College community to higher standards of awareness and accountability to racial power dynamics both inside and outside the classroom. In making the history of the College’s engagement more accessible, Emma and I hope for two things: first, that the community can use our work as a resource to address the recycling of traumas that recurs every few years as students graduate and fruits borne of past conversations gather dust, or disappear. Second, we hope to actively encourage awareness of Black experiences at the College and to provide a metric by which Bryn Mawr can ascertain its progress over time.

Given the uncanny similarities between 1988-1989 and 2014-2015, however, the usefulness of the term “progress” to describe Bryn Mawr’s momentum toward racial equity may seem suspect. Sitting in the archives, it is tempting at times to feel as though history has little use beyond its effectiveness as a rhetorical tool for pointing one finger at the past and another at the present in order to draw attention to the seemingly anachronistic nature of current problems. Admittedly, Why are Bryn Mawr students still fighting the same kinds of issues that students rallied against 25 years ago? is not so much an argument as it is an expression of frustration and disbelief.

But there are lessons to be learned from the past. Campus-wide conversations in 1988-1989 wrought real reforms. Dialogue sparked important institutional changes. President Cassidy’s plan to host the Community Day of Learning annually is a much-needed step toward ongoing community dialogue that transcends boundaries between students, faculty, and staff. Digital history projects, like Black at Bryn Mawr, promote sustainable dialogue by providing a resource for cross-generational remembrance and understanding.

Above all, a study of Black history at Bryn Mawr reveals that students — especially students of color — have consistently driven the changes that have made the College what it is today. But college should be a time for personal growth, not a time when students of color are saddled with the burden of confronting ignorance. All Bryn Mawr students should be proud to be part of a school that has graduated strong, fiercely determined students like Rivera. Honoring Rivera’s legacy, however, entails responsibility. Hers is a legacy that can only be honored by fighting to make the College a space where the diverse experiences and contributions of our peers are respected fully and all students challenge and support each other to be the best they can be.

* * *

Suggested Reading:

Bryn Mawr Communications Office, “Campus Comes Together for Community Day of Learning,” March 20, 2015.

#BlackatBrynMawr live Twitter feed from the Community Day of Learning, March 18, 2015.

Huntly Collins, “Student Conference Focuses on Campus Racial Problems,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 6, 1988.

Huntly Collins, “Bryn Mawr Battles Bigotry on Campus,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 12, 1989.

- Huntly Collins, “Student Conference Focuses on Campus Racial Problems,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 6, 1988. Accessed April 4, 2015. http://articles.philly.com/1988-11-06/news/26248254_1_student-conference-minority-students-white-students [↩]

- Memo from Deans to Bi-College Community, October 8, 1988, Box 9JAF, “Diversity,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Diane Garrett, “Racism Alive on Campus,” Main Line Sunday, Vol. 6, No. 36, October 22, 1989, Box 9JAF, “Diversity — Newspaper Clippings,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Huntly Collins, “Bryn Mawr Battles Bigotry on Campus,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 12, 1989, accessed April 4, 2015, http://articles.philly.com/1989-02-12/news/26152430_1_workshops-student-petition-incidents. [↩]

- “List of Black Undergraduate Alumnae,” Box 9JAF, “Diversity — African American Students Through 1979,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Chronology adapted from Nan Harris, “Pluralism and Diversity at Bryn Mawr: A Talk Given to the Bryn Mawr Club of Boston on May 25, 1989 by Nan Harris, President of the Alumnae Association,” May 25, 1989, Box 9JAF, “Diversity,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA, which cited an article printed in The College News, March 31, 1989. [↩]

- Diane Garrett, “Racism Alive on Campus,” Main Line Sunday, Vol. 6, No. 36, October 22, 1989, Box 9JAF, “Diversity — Newspaper Clippings,” Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- “Campus Comes Together for Community Day of Learning,” Bryn Mawr College News Bulletin, March 20, 2015, accessed April 4, 2015, http://news.brynmawr.edu/2015/03/20/campus-comes-together-for-community-day-of-learning/. [↩]