by Emma Kioko

Note: This is the second of a two-part post about the climate of racial activism on campus between 1970 and 1972. The two posts center on two events: the “near sit-in” of March 12 (1970) and the first fight for Perry House (1972). Woven through both events are incredibly intelligent and nuanced discussions of race introduced and led by students including Bryn Mawr’s Sisterhood. These women paved the way for truly engaged activism on campus and their efforts should be celebrated and remembered. Read Unwavering Dissent Part I here.

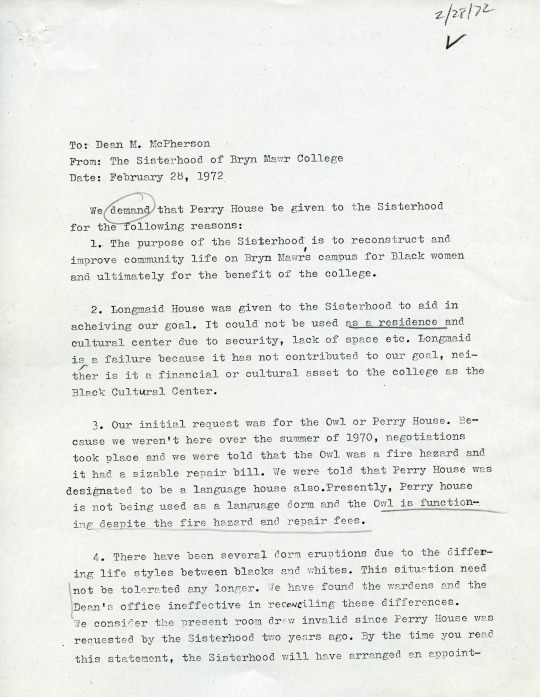

Sisterhood letter, 1972 (to view second page, visit the Greenfield Digital Center tumblr).

A Demand for Space in 1972

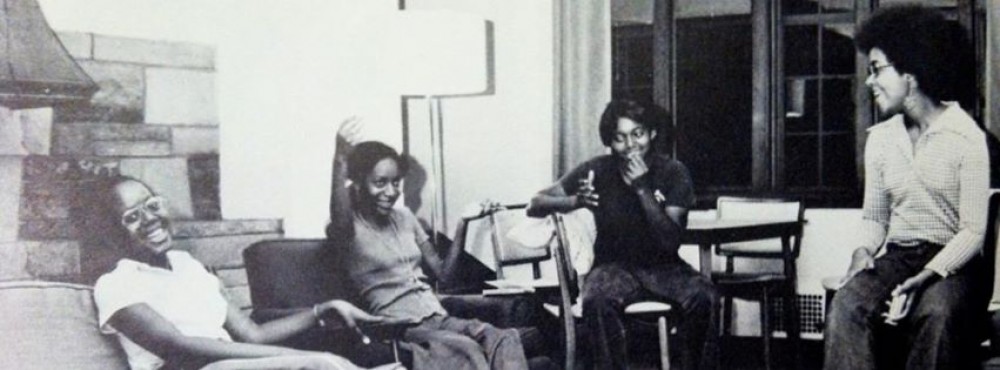

The fall of 1970 welcomed a new perspective on race relations at Bryn Mawr in the form of a new president, Harris Wofford. This new president seemed genuinely interested in fostering better lines of communication between students of color and the administration. In a speech at Convocation in 1970 he said, “The antidote is a deep respect for persons, an enjoyment of differences, and a robust readiness for dialogue.” At the beginning of each academic year President Wofford reached out to the women of Sisterhood and reaffirmed his commitment to them and all black students on campus. However, the black women on campus were still missing something they regarded as incredibly important to their mission of creating community and celebrating culture: an adequate cultural space.

Given to them after their initial demands in 1970, Longmaid House, located at a far edge of campus close to Batten House, was wholly unacceptable as a cultural center. Constant flooding and security problems with the old building made it unsuitable for residence and completely useless as a display space for art. Racial tensions were high in the dorms, and the black women of Bryn Mawr were fed up with the conditions of Longmaid. In addition to the conditions of Longmaid House, the women of Sisterhood observed that Perry House, the space they had originally requested and been told was already contracted as a language house, was not being utilized as a language house at all. Owl House, their second choice, which they had been told was a fire hazard in 1970 and unusable, was being used in spite of the repair fees. These inconsistencies did not add up. Had the administration lied years before for the sole purpose of not giving up Perry or Owl as Black Cultural Center? Unwilling to sit silent, they began crafting a new list of demands for a safe space on campus in 1972.

On February 28, 1972, the women of Sisterhood issued to Dean McPherson and President Wofford a demand for Perry House.

They wrote:

We demand that Perry House be given to the Sisterhood for the following reasons:

- The purpose of the Sisterhood is to reconstruct and improve community life on Bryn Mawr’s campus for Black women and ultimately for the benefit of the college.

- Longmaid House was given to the Sisterhood to aid in achieving our goal. It could not be used as a residence and cultural center due to security, lack of space etc. Longmaid is a failure because it has not contributed to our goal, neither is it a financial or cultural asset to the college as the Black Cultural Center.

- Our initial request was for the Owl or Perry House. Because we weren’t here over the summer of 1970, negotiations took place and we were told that the Owl was a fire hazard and it had a sizable repair bill. We were told that Perry House was designated to be a language house also. Presently, Perry House is not being used as a language dorm and the Owl is functioning despite the fire hazard and repair fees.

- There have been several dorm eruptions due to the differing life styles between blacks and whites. This situation need not be tolerated any longer. We have found the wardens and the Dean’s office ineffective in reconciling these differences. We consider the present room draw invalid since Perry House was requested by the Sisterhood two years ago…

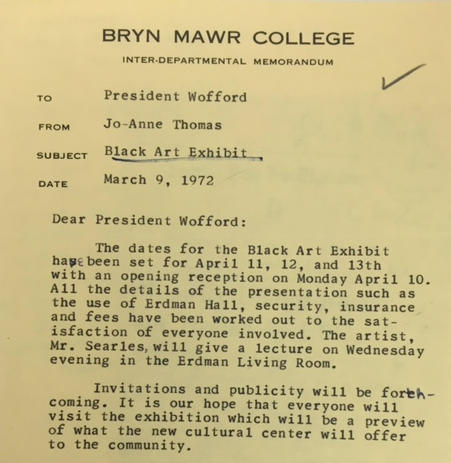

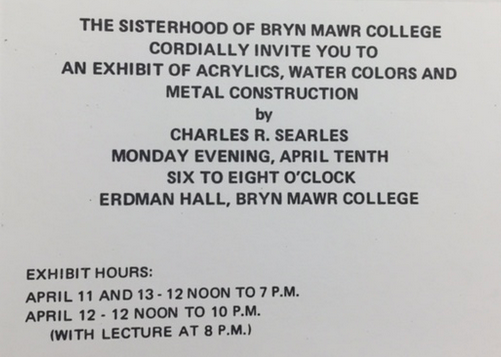

A Black Art Exhibit for Erdman Hall

By March 8th, President Wofford and his administration had promised the Sisterhood Perry House for their cultural center. To showcase the type of programming would be possible in the new cultural center, the Sisterhood organized a Black Art Exhibit for Erdman Hall to be available for the community to view in mid April of the same semester. The artist, Charles Searles, would be coming to the college on Wednesday April 12 to give a lecture on his work. Sisterhood sent out formal invitations to both President Wofford and Dean McPherson via the assistant dean of student affairs.

To the surprise of Sisterhood’s members, neither the president nor the dean came out to see the exhibit. In a letter to the president, members of Sisterhood wrote:

President Wofford:

We, the members of the Sisterhood would like to express our shock and disappointment that only two members of the administration found it possible to attend the opening of the Charles Searles exhibit. We understand that many of you may have had previous commitments, yet it was surprising that so many of you failed to attend. Certainly, a note to the Sisterhood expressing your regrets would have been in order. The Charles Searles exhibit represents a unique cultural opportunity that one seldom can experience here at Bryn Mawr College. In light of this fact and your stated interest in the activities of the Sisterhood, a reasonable representation from the administration had been expected to attend. The issue in this case is not etiquette but credibility. Do you seriously care to experience other cultural expressions? If you do not, then it would be appropriate for the Sisterhood to close their cultural affairs in the future, given this understanding.

The unfortunate absence of President Wofford and Dean McPherson from Sisterhood’s exhibit must have struck a very sensitive nerve. The exhibit was meant to be a celebration of the administrations long awaited acknowledgement of the importance of black culture and expression on campus. For years, the black women on campus saw their culture relegated to unsuitable, unsecure, and peripheral spaces on campus and even, sometimes, no space at all. In finally promising black women a space within which to share and celebrate their culture, President Wofford created a fresh image for the administration. Not showing up to the exhibit, told the women of Sisterhood that the administration was not ready to change completely.

Convocation 1972

The granting of Perry House to the Sisterhood was a good start, but it was clear to the black women of Bryn Mawr that there were many more steps to be taken for adequate change. Nowhere are the racial tensions on campus more obvious than a Convocation speech given by Rikki Lights, on behalf of the Sisterhood, on April 9, 1972:

I presume that I am here to give you all some idea of racism or to speak to that specific point. I am not sure if this speech is in vain; I am not even certain that you all, as a conditioned pack of upper middle class whites with an enormous superiority complex are capable of even listening to, much less dealing with the institutionalization of racism that, to me, is so very blatant at Bryn Mawr College. As to the feminist origins of Bryn Mawr College, I do not separate you white women from white men. You are one in the same; oppressors. White women are not, I repeat, are not less prejudiced; no less the perpetuators of this oppressive government than are the white men they marry, or the little white babies they rear to be just like their racist forefathers.

Racism is a state of mind. It is the state of mind that made your saint-mother M. Carey Thomas see that white elitist women wanted to compete with Harvard and Yale men; but to ignore the fact that Black men and women needed freedom to think; allowed her to ignore the fact that for a Black to read a book in places in the South; or to even try to teach in Philadelphia was enough justification for whites to take the life of that Black person. Racism caused the shock and speculation at the first Black woman to step foot on this campus. Racism is the state of mind that told the president of this college, who was then a woman, and the rest of the administration to tell her that she could not live on campus. They did not want her to contaminate the lily whiteness of Bryn Mawr College. The student body did not protest this.

Lord, need we mention how you Bryn Mawrters have for years treated the maids like they were/are pure shit; leaving your filth for them to clean up, calling them by their first names! How dare you call Mr. Russell, “Jake?” You pretend you can’t understand why Blacks protest.

Racial and economic prejudice fostered the policy that scholarship students should live in the cheapest rooms when Blacks were finally allowed to live on campus. The intolerance of behavior and lifestyles of Blacks, and the sometimes outright harassment of Black students and/or others who are just different are obvious signs of bias.

Bryn Mawr not only is racist; it is ingrown! People here did not even think this place should make political decisions.

You witnessed the lack of thought given to the People’s Peace Treaty last year. One student in Haffner Hall had the audacity to say “After all what can we do, we’re only women, our parents send us here to study not to get involved in political decisions.” This was by far the sentiments of the majority of the people in Haffner. As if Bryn Mawr, by being elitists, has not already made a political decision! Honoring Hannah Arendt as a great woman is racist — Hannah Arendt is an exceedingly biased political scientist; Bryn Mawr, by honoring her, agrees with what she has to say about the “nonexistence of black literature.” Bryn Mawr further reiterates this bias, or should I call it the absolute stupidity, by not stocking its library with books by Black political scientists, Black economists, Black novelists, Black poets; the thinkers of this century. Your sheltered minds have been dragged into believing that Black thinkers do not exist; and that there are no qualified Black people to teach political science or philosophy. To be ignorant is to allow the oppression, so carefully designed in Congress and perpetuated in Bryn Mawr College, to continue. If you don’t believe that this institution echoes the political fads of the country, remember the articles about the trip to China that Bryn Mawr wants to make; and that was initiated in the heart of Mr. Nixon’s trip to China. Bryn Mawr College does not even have Chinese culture, art, or philosophy as a separate discipline nor does it offer it extensively in any of its departments.

Ms. McPherson, you asked about finding out the female truth; as you stated in the discussion on racism during the colloquium. The white female truth should be to perceive correctly herself, men, and those outside her. You will never achieve a female truth if you continue to do nothing about racism and ignorance with respect to the outside world, that I see in the women at Bryn Mawr College. If you are sincere about learning the woman’s truth, tell the truth in your classroom. Tell how the Greeks stole their philosophy from the Egyptians; include Dr. Josef Ben-Jochannan’s books on African philosophy and philosophers. The truth needs to be told in the Music department, in the Anthropology department, in the Financial aid office and at the desk of every professor as she/he prepares the class agenda.

Blackness through black women exists on this campus. Ignorance considers it invalid. Ignorance and malevolence will not allow it to be recognized or taught. Blackness is not a fad; it is a reality. It is one that must be reckoned with. You are quietly living like court jesters in elitist land believing in Honor Codes when everybody knows that it does not mediate racial, cultural, or religious differences. The Honor Code cannot, as it stands, eradicate racism, because to do so requires a knowledge of others that women at this college do not possess. Educate yourself to the realities of life first, then you can talk about honor codes; and only then can you begin to find and practice the woman’s truth.

On the heels of the administration’s promise for Perry, April 1972 quickly became a month of activism among students and alumnae at the college.

Black Admissions

Combing through the archives, it becomes clear that racism on campus went beyond student interactions and the overall racial climate on campus. Bryn Mawr’s prejudices were showing through its admissions practices. In a letter to Betty Vermey, the Director of Admissions, Joanne Doddy outlined the ways in which Bryn Mawr’s black admissions tactics and strategies were racist and unfair. Informing Ms. Vermey of her boycott of recruiting events, on April 12, 1972, Ms. Doddy wrote:

Dear Miss Vermey:

I am writing to inform you that I can no longer in good conscience represent Bryn Mawr to Black women candidates in any phase of the recruiting and admissions process… I am also encouraging Nell Lokey to join me in my stance and forego her scheduled trip to New York on April 29th. I have made this decision as a result of the actions taken by the Admissions Committee this year on black applicants. I have not seen any indication of a serious commitment on the behalf of the college- from the faculty to the admissions office to the president- to increasing the number of black students on campus… the subjective nature of the admissions procedure resulting from the lack of written standards and a written commitment from the school to the increasing of black students forces the participants in the admissions process to act out their own biases.

At college day programs… many of the black women are within the top ten percent of their classes and have on their own participated in extra programs to enrich their high school education. I have previously encouraged this type of student who has proven herself to be highly motivated to apply to Bryn Mawr with the hope that the college would consider past performance as a better indicator of ability than the aptitude tests which are currently being questioned as to their accurate predictive nature in terms of minority students.

It is clear to me now that Bryn Mawr has no such commitment to this type of student. And it is this very lack of commitment which is responsible for the decrease in the number of black applicants and the decrease in the number of black students entering the college. It has virtually institutionalized the acceptance of a low percentage of minority students, an action which consequently reduces the cultural diversity on campus.

If Bryn Mawr has no intention of accepting a student, she should not make the pretence of recruiting her. It is a waste of time and money. This college is too quick to attempt to preserve its liberal facade by sending a black student of black dean to keep up good appearances while evading the real commitment to hiring a full time black recruiter for minority students. The college has exploited a few of us in terms of time, energy and money to maintain a liberal image which it does not merit.

I refuse to give false hopes to talented black women who have proved that they have the dedication, motivation, and interest to succeed- frequently against immeasurable odds. I refuse to project a commitment that Bryn Mawr is not willing to support. And I will actively encourage the other black women on campus to refrain from attending recruiting programs as Bryn Mawr’s representative until such a time as Bryn Mawr sees fit to hire a full time black admissions officer and makes a written commitment to accepting minority women as at least 10% of each incoming class using whatever standards necessary to achieve that goal.

Committed to a struggle,

Joanne L. Doddy

Conclusion

The promise of Perry House was just the beginning of tangible institutional change at Bryn Mawr College. Upon moving into Perry House in the fall, a new saga of unsuitable living conditions would become an issue for the women of Sisterhood. However, a space to call their own, for expression, reflection, and celebration of their culture would prove to be invaluable. A publication called ‘Ra,’ an all-black magazine distributed to the community and beyond (including UPenn and Morehouse), yearly community wide cultural arts programming, and a student-curated library would find a home in Perry House. The women of Perry House took note of the ways in which their administration was failing them and took the difficult steps to enact meaningful and tangible change.

Notes

All cited material located in Sisterhood Folder, box 9J-AF, 9JAF, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Pingback: Black at Bryn Mawr and the Enid Cook ’31 Center at Bryn Mawr College | Black at Bryn Mawr