by Emma Kioko

Note: This is the first of a two-part post about the climate of racial activism on campus between 1970 and 1972. The two posts center on two events: the “near sit-in” of March 12 (1970) and the first fight for Perry House (1972). Woven through both events are incredibly intelligent and nuanced discussions of race introduced and led by students including Bryn Mawr’s Sisterhood. These women paved the way for truly engaged activism on campus and their efforts should be celebrated and remembered.

Read Part I here now and don’t forget to check back to read the second post: Unwavering Dissent Part II: Challenging the Rhetoric of Racism in 1972 and the First Fight for Perry!

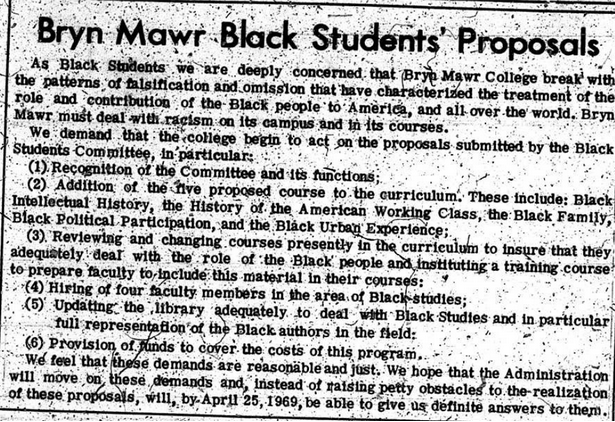

Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, April 15, 1969. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

An Initial Upset in 1970

We shall find you a house for a cultural center. As you know the Spanish house by a two-year old agreement is currently being planned as a Russian house. We shall nevertheless find a house and I understand that it will be as are all residence halls open to students on invitation, white or Black…

-President Katherine E. McBride

The Black women of Bryn Mawr College were upset. In the 1968-1969 academic year, concerned with Bryn Mawr’s academic and administrative “patterns of falsification and omission that characterized the treatment of the role and contribution of the Black people in America, and all the world,” a group of students created the Black Students Committee to review the status of Black Studies on campus. In Spring 1969 the committee issued a list of curricular proposals in the hopes of forcing Bryn Mawr to acknowledge “racism on its campus and in its courses.”1 The “reasonable and just” proposed changes were given with an action deadline of April 25, 1969.

Among the list of demands were the addition of five new courses to the curriculum (Black Intellectual History, the History of the American Working People, the Black Family, Black Political Participation, and the Black Urban Experience), the hiring of four Black Studies professors, and updating the library’s offerings to adequately represent Black authors and intellectuals. Student reactions to the delivered proposals were well documented in the newly established Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, and many of the reactions were supportive of the proposed program and changes. An editorial in the April 15, 1969 edition of Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News reads:

The proposals made by the black students at Bryn Mawr are just and worthy of immediate approval by the College’s administration and faculty. The proposals are not at all ‘radical.’ They do not deal with increased black admission. They are only concerned with achieving greater recognition in the curriculum of specifically black problems so as to better enable all students to understand black Americans’ past and present.2

Another editorial published on April 22, 1969 (just before the April 25 deadline) read,

Action on the demands hinges on the continuation of cooperation among the committee members and the administrators, that means carrying out the proposals, not just continuing their dialogue.3

Despite widespread student support, on April 25 the demands remained largely unfulfilled by President Katherine McBride’s administration. On April 25, Mindy Thompson ‘71 wrote in an article, “Bryn Mawr can only look forward to a Black Studies program if the administration begins to do two things: hire faculty, and take a stand on Black Studies, endorsing it publicly and privately.”4 Perhaps the women’s list of demands were unfulfilled by the administration due to the largely academic and curricular aspects of their demands. Demands for faculty and courses could have been limited by the resources and openings available at the college at the time. President McBride later wrote that any concerns and suggestions about curriculum or faculty hiring would have to go through proper channels and procedure; these were apparently not issues the President’s office could fix overnight.

The message behind the administration’s noncommittal response was clear to the Black students of the College. Anything they wanted to get out of Bryn Mawr, they would have to fight for, loudly.

***

Unwavering, on March 12, 1970 at 12 o’clock noon, a group of 35 black students and 45 white students marched to visit President McBride and deliver another, longer, and more specific list of demands. ((The 45 white students belonged to the Women’s Studies Committee.)) President McBride agreed to listen to the statement. Fed up with institutional silencing, these brave women took direct action, making sure their message would be heard by the administration directly, and issued a list of ten demands that ranged from an increase in non-menial Black employment and the appointment of Black professors to the allocation of transportation funds for African languages at Penn and the creation of a cultural house.

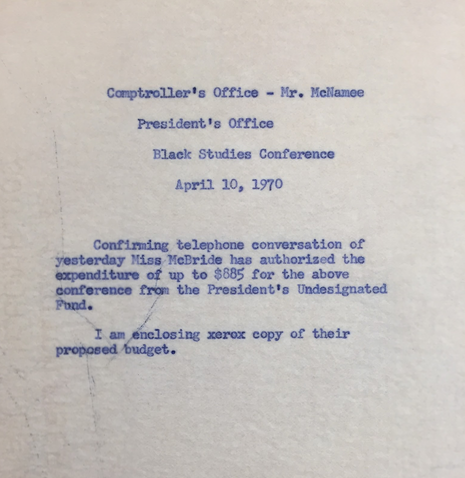

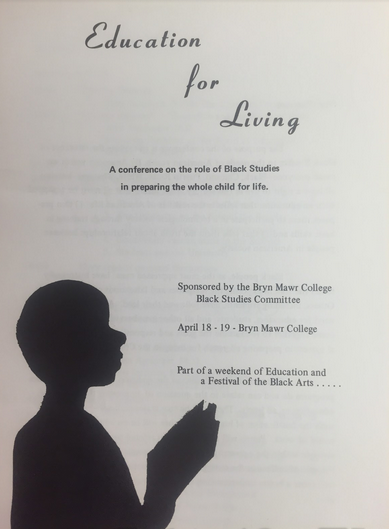

What was the outcome of these students’ efforts on March 12th? Well, perhaps the answer that best characterizes President McBride’s response lies in the money. Not long after the “near sit-in” of March, President McBride confirmed two separate withdrawals from the “President’s Undesignated Fund” for Sisterhood and Bi-Co Black Student League events. On April 9, 1970 President McBride authorized the comptroller via telephone to allocate $885 to the Sisterhood’s Black Studies Conference.5 On April 14th, she authorized another $200 for the Bi-Co Black Student League’s annual Black Arts Festival (an annual event that was already planned for that very weekend: the weekend of April 18th.)6

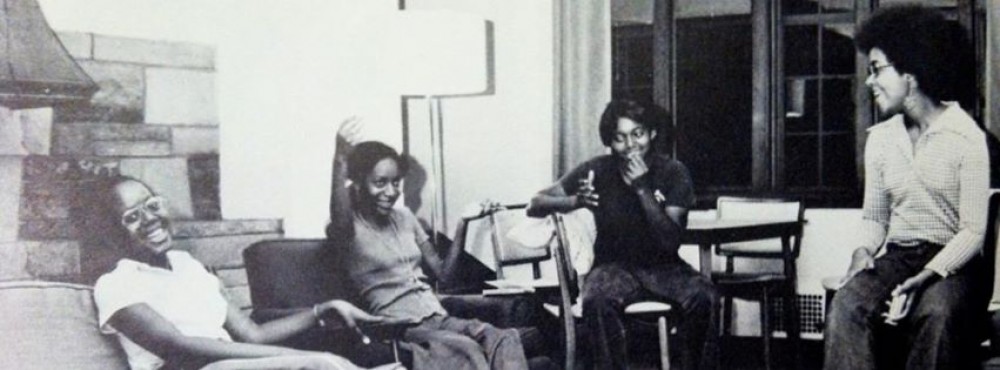

Box 9JAF, Diversity — African American, Sisterhood, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Box 9JAF, Diversity — African American, Sisterhood, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

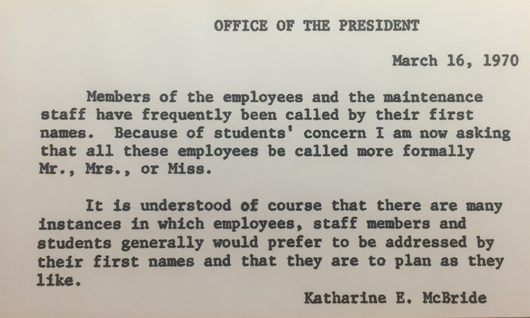

According to the Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News issue published March 13, 1970, “Miss McBride presided over the group and gave consent to all provisions of the statement.”7 In addition to the monetary allowances, the Black students were adamant about more respectful treatment of College staff (who were mainly Black.) On March 16th, just a few days after the events of March 12, President McBride issued an official statement:

Box 9JAF, Diversity — African American, Sisterhood, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Also among the provisions McBride agreed to work on was the creation of a “summer program for incoming students who need additional academic preparation before beginning their regular studies at Bryn Mawr,” increasing the number of sociology professors (one of which was to be Black), and a new plan for Black enrollment to the College.8 Where the demands of 1969 had been ignored, it seems that (at the very least) the demands of 1970 were taken seriously. In taking action and activism into their own hands, it seems that the Black women of March 12 were able to enact tangible changes, however small, in their community. Combing through the archives, it becomes increasingly apparent that the events of March 12 had an effect on the entire campus. The demands and promises affected not only the administration but students and faculty as well. On May 1st of the same semester, Professor Richard DuBoff (Economics) published an article in the college newspaper titled “Answers to Black Demands Made Without Approval of Econ. Dept.” Many Black students on campus were under the impression that President McBride had promised that the next appointment in Economics would be Black.9 In his article, Professor DuBoff answers back to the reports that in issuing her promises, McBride failed to ever consult the members of the Economics Department. He wrote, “This promise and-or action was taken with no consideration of the likelihood that the economics department can find and hire any black economist, let alone a well qualified one… a search for a black economist (which we’ve undertaken in the past and will pursue again in the future) stands only a very small chance of success.”10 While no Black economics professor would be hired, McBride’s promise regarding the Sociology Department was fulfilled with the arrival of Professor Robert Washington in 1971. Despite unrest in Economics, the Black women who came together made their demands a reality through careful planning, determination, and most importantly, commitment to a struggle that would continue well beyond their time on Bryn Mawr’s campus.

***

Before concluding part one of this two-part post, I would nonetheless like to mention a bit of research that is still unfinished, but important to this case (in particular the upcoming part two.) One of the demands issued on March 12 was the creation of a cultural house. They initially requested Spanish House (Perry House) but were told by President McBride that Spanish House was slated to become Russian House by a 2 year-old agreement. My research leads me to believe that the students of the Sisterhood were given Longmaid House as a result of the March 12 demonstration, although I have been unable to find sufficient evidence for this claim. What we do know is that on March 12 they demanded a cultural center and in her response to their demands, President McBride definitively promised a center. Later, in 1972, we know that students of the Sisterhood protested the conditions in Longmaid House (which was in such disrepair it was considered useless as both a cultural center and residence) to President Wofford. Longmaid House, located at 1000 New Gulph Road near the Batten property, would go on to play an important role in the first fight for Perry in 1972.

Conclusion

The unwavering efforts of the Black women in 1970 who worked hard to carve out a space for themselves and their successors at Bryn Mawr College are unforgettable. They dared to speak out against the behemoth of institutional academic racism. They demanded Black faculty, Black Studies courses, respect for often-trivialized staff members, and perhaps most importantly, a space to call their own in the form of a cultural center. In the face of Bryn Mawr’s bureaucratic administration, they took actions that would not only be noticed but taken seriously. Do aspects of their concerns resonate on campus today? Certainly. Hiring faculty of color and encouraging diversity of academic thought is still something that this campus struggles with today. Perhaps the most chilling experiences for me while researching this small episode in Bryn Mawr’s history were in the ways that a lot of the Bryn Mawr experience as a person of color has not changed. Yet is is without doubt that these women played a large role in laying the foundation for a more honest, educated, and racially conscious Bryn Mawr. These students, the Black women of Bryn Mawr College, refused to accept the marginalization of the Black experience at Bryn Mawr and theirs is a legacy that still echoes in the hallways, classrooms, and greens of our campus today.

- 9JAF Diversity African-American, Sisterhood, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, April 15, 1969. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, April 22, 1969. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, April 25, 1969. [↩]

- 9JAF Diversity — African American, Sisterhood, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- “Black Students and Alumnae Speak,” Bryn Mawr Alumnae Bulletin (Spring 1969), 9JAF Diversity — African American, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, March 13, 1970. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, March 13, 1970, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

- Nota Bene: At this time there is no written proof that an Economics position was promised explicitly by President McBride or any of her staff. In the spring of 1970, there was question as to whether or not the promise was made on paper, word-of-mouth, or was simply rumor. Certainly she encouraged student input on the hiring process, but there does not appear to be a way to corroborate that such a promise was made to the students. Despite this, the knowledge that a promise (of some form) had been made was powerful enough to cause unrest among the professors of Economics, none of whom were consulted for information on the hiring status of the department. [↩]

- Bryn Mawr and Haverford College News, May 1, 1970, Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA. [↩]

Pingback: Black at Bryn Mawr and the Enid Cook ’31 Center | Black at Bryn Mawr