by Grace Pusey

Content Warning: This post contains racist slurs.

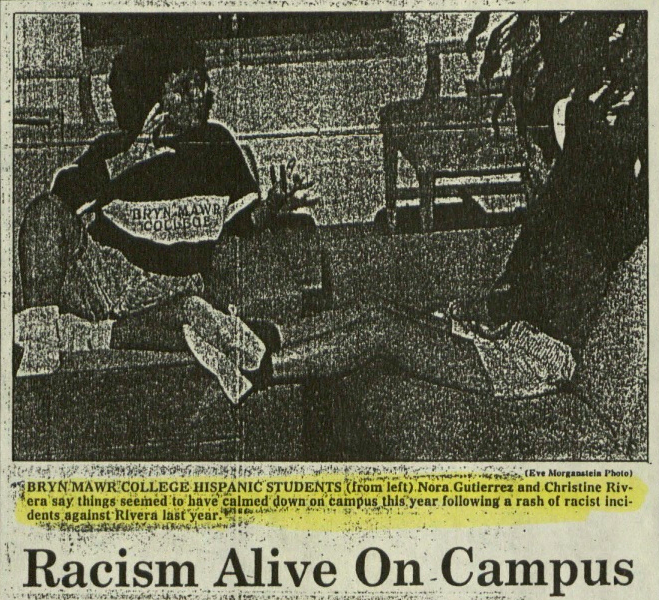

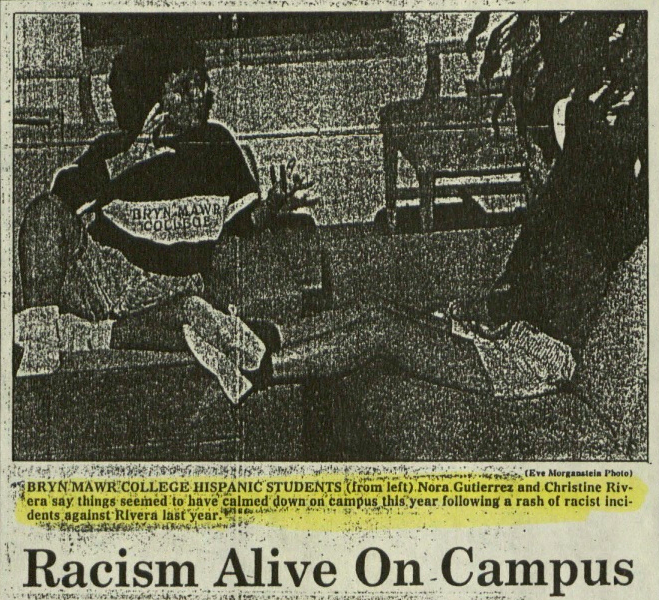

“Bryn Mawr College Hispanic students (from left) Nora Gutierrez and Christine Rivera say things seemed to have calmed down on campus this year following a rash of racist incidents against Rivera last year.” Diane Garrett, “Racism Alive on Campus,” Main Line Sunday, Vol. 6, No. 36, October 22, 1989. Bryn Mawr College Special Collections, Bryn Mawr, PA.

ON OCTOBER 7, 1988, first-year student Christine Rivera returned to her dormitory to find an anonymous note slipped under her door. “Hey, spic,” it read, “Why don’t you leave Bryn Mawr? If you and your kind can’t handle the work here, don’t blame it on this racial thing. You’re making our school look bad to everyone else. If you can’t handle it, get out. We’d all be a lot happier.”

Rivera reported the note immediately. College administration responded swiftly, issuing a memo to students, staff, and faculty the next day. “We want to make it very clear that prejudice, harassment, and discrimination will not be tolerated in the bi-college community,” it read. “They represent the antithesis of the values essential to our basic mission: pursuit of knowledge in a free and open atmosphere where differences of opinion, background, and belief are valued and respected. […] [Until] everyone in our colleges — students, faculty, and staff — is free from harassment and discrimination here, we have failed to live up to our principles.” The memo concluded by urging the perpetrator of Rivera’s harassment to turn herself in to the Honor Board, or to his or her immediate supervisor if they were College staff.

No one came forward, however, and the abuse continued. First, Rivera found a paper she had written for an English course slipped under her door with a slash through her last name. Then she discovered a decoration that she had hung on her door ripped to shreds and slipped underneath it. “I was very fearful of walking through my door,” Rivera later admitted in an article published in Main Line Sunday a year after the initial verbal attack,but she did not report these incidents at first. Unwittingly placed at the center of an unfolding campus scandal, she “[…] didn’t want to cause any more tension.” Because the identity of Rivera’s harasser remained unknown, all the controversy was drawn to her. Some students, unable to fathom how such a vitriolic note could have been written by anyone at an institution with a “liberal, open-minded” reputation like Bryn Mawr’s, even believed Rivera was faking her own harassment.

Continue reading →